C-Audio-Player

Project Overview

This project is a simple audio player implemented in C, providing both synchronous and asynchronous playback capabilities. It offers basic controls for audio playback, including play, pause, resume, volume control, and stop functionality.

{

// ...

play_sync("sound.mp3", 100);

printf("This is printed after sound.mp3 is done\n");

play_async("sound2.mp3", 50.5);

printf("This is printed while sound2.mp3 is playing\n");

// ...

}

Features

- Synchronous and asynchronous audio playback

- Pause and resume functionality

- Volume control

- Ability to stop playback

- Monitor playback state

API Documentation

The Simple Audio Player exposes the following API:

Initialization and Cleanup

void init_ao(); void destroy_ao();

init_ao(): Initialize the audio output system. Must be called before using any other functions.destroy_ao(): Clean up and release resources used by the audio output system. Should be called at the end of the program.

Playback Functions

int play_sync(const char *filename, double volume); t_sound *play_async(const char *filename, double volume); // Volume is any double between 0 and 100, values out of range are scaled back

play_sync(): Play an audio file synchronously. Returns-1on error.play_async(): Start asynchronous playback of an audio file. Returns a pointer to at_soundstructure orNULLon error.

Playback Control

int running_sounds(t_action action, t_sound *sound);

running_sounds(): Control playback of a sound. Theactionparameter can be one of the following (returns-1on error):

1- PAUSE: Pause the playback.

2- RESUME: Resume paused playback.

3- STOP: Stop the playback and clean up resources.

(IMPORTANT: After STOPing a sound, the matching t_sound instance is completely destroyed. Any usage of the variable after this will result in an undefined behavior)

int set_volume_value(t_sound *sound, double value);

set_volume_value(): Sets the sound’s volume.valueshould be0 <= value <= 100.

Monitor playback state

t_state get_state(t_sound *sound);

get_state(): Returns the state of a sound. Thet_statereturn type is one of the following:

1- PLAYING: Currently playing.

2- PAUSED: Currently paused.

3- END: Playback has ended.

4- ERROR: Error occured while checking state.

Examples

// Include the header file #include "simpleaudio.h" // You should always call these two functions ONCE to initialize // and destroy output resources at the beginning and end of your // code respectively. int main(int ac, char **av) { init_ao(); // Your code goes here destroy_ao(); }

Playing an audio file synchronously with max volume, taken from the commad line arguments:

int main(int ac, char **av) { init_ao(); int ret = play_sync(av[1], 100); if (ret == -1) printf("error\n"); destroy_ao(); }

Same, but async:

int main(int ac, char **av) { init_ao(); t_sound *sound = play_async(av[1], 100); if (sound == NULL) printf("error"); destroy_ao(); }

You can then manipulate the playing sound using the t_sound instance you have, you can pause, resume, change volume and stop:

int main(int ac, char **av) { init_ao(); t_sound *sound = play_async(av[1], 100); if (sound == NULL) printf("error"); // Pause if (running_sounds(PAUSE, sound) == -1) printf("error"); // Resume if (running_sounds(RESUME, sound) == -1) printf("error"); // Change volume to 25% if (set_volume_value(sound, 25) == -1) printf("error"); // Stop if (running_sounds(STOP, sound) == -1) printf("error"); destroy_ao(); }

We’ll add some sleep() functions to observe sound’s changes. Our full program would be:

#include "simpleaudio.h" #include <stdio.h> int main(int ac, char **av) { init_ao(); printf("Let's play audio\n"); t_sound *sound = play_async(av[1], 100); if (sound == NULL) printf("error"); sleep(1); // Pause printf("Let's pause\n"); if (running_sounds(PAUSE, sound) == -1) printf("error"); sleep(1); // Resume printf("Let's resume\n"); if (running_sounds(RESUME, sound) == -1) printf("error"); sleep(1); // Change volume to 25% printf("Let's change volume\n"); if (set_volume_value(sound, 25) == -1) printf("error"); sleep(1); // Stop printf("Let's stop\n"); if (running_sounds(STOP, sound) == -1) printf("error"); sleep(1); destroy_ao(); }

Lastly, you can wait for an async playback to end, like this:

{

// ...

// wait for playback to end

while (get_state(sound) != END)

usleep(1000); // adjustable

// ...

}

How to use

Install locally

First, you need to install two dependencies that the library needs:

sudo apt-get install libao-dev libmpg123-dev

Clone repo

Then clone this repo locally:

git clone https://github.com/saad-out/C-Audio-Player

cd C-Audio-Player

Building the library

Once you’ve cloned the repository, you can build the library using the provided Makefile:

This command will compile the source files and generate static libsimpleaudio.a library in the lib/ directory.

Linking with your program

To use the library in your own program, you need to include the header file and link against the library.

1- Copy the include/simpleaudio.h header file to your project directory or add the include/ directory to your include path.

2- Copy the lib/libsimpleaudio.a file to your project directory or a directory in your library path.

3- In your C file, include the header:

4-Compile your program, linking it with the Simple Audio Player library. Here’s an example compilation command:

gcc -o your_program your_program.c -L. -lsimpleaudio -lmpg123 -lao -lpthread -lm

Make sure to replace your_program and your_program.c with your actual program name and source file.

Note: The -lmpg123 -lao -lpthread -lm flags are necessary because our lib depends on these libraries. Make sure you have them installed on your system.

Docker image

This Docker image contains the Simple Audio Player library, allowing you to easily compile and run C programs that use this library.

Pulling the Image

To pull the image from Docker Hub, use the following command (you might need to use sudo):

docker pull saadout/simple-audio-player:latest

Using the Image

1- Create a C file that includes the Simple Audio Player library. For example, program.c:

#include <simpleaudio.h> #include <stdio.h> int main() { printf("Simple Audio Player library is successfully included!\n"); return 0; }

2- Run a container from the image, mounting your current directory:

docker run -it --rm -v $(pwd):/app saadout/simple-audio-player

3- Inside the container, compile your program:

gcc -o program program.c -lsimpleaudio -lmpg123 -lao -lpthread -lm

4- Run your program:

Automating Compilation and Execution

You can use the following command to compile and run your program in one step:

docker run -it --rm -v $(pwd):/app saadout/simple-audio-player sh -c "gcc -o /app/program /app/program.c -lsimpleaudio -lmpg123 -lao -lpthread -lm && /app/program"

Replace program.c and program with your actual file names if different.

Note

This image is based on Ubuntu and includes all necessary dependencies to compile and run programs using the Simple Audio Player library.

Здравствуйте! В этой статье мы рассмотрим, как создать простое приложение для воспроизведения музыки с использованием класса SoundPlayer в C# Windows Forms. SoundPlayer — это часть пространства имен System.Media, которая позволяет воспроизводить звуковые файлы в формате WAV. Хотя SoundPlayer поддерживает только WAV-файлы, это отличный способ начать работу с аудио в .NET.

Шаги для создания музыкального плеера

- Создание нового проекта Windows Forms:

- Откройте Visual Studio.

- Создайте новый проект и выберите «Windows Forms App (.NET Framework)».

-

Назовите проект, например, SimpleMusicPlayer.

-

Добавление элементов управления:

-

Добавьте на форму следующие элементы управления:

- Button для запуска воспроизведения музыки.

- Button для остановки воспроизведения музыки.

- OpenFileDialog для выбора WAV-файла.

-

Использование SoundPlayer для воспроизведения музыки:

- Создайте экземпляр SoundPlayer и используйте его для управления воспроизведением.

Пример кода

using System;

using System.Media;

using System.Windows.Forms;

namespace SimpleMusicPlayer

{

public partial class Form1 : Form

{

private SoundPlayer player;

public Form1()

{

InitializeComponent();

}

private void btnOpenFile_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

using (OpenFileDialog openFileDialog = new OpenFileDialog())

{

openFileDialog.Filter = "WAV Files|*.wav";

if (openFileDialog.ShowDialog() == DialogResult.OK)

{

player = new SoundPlayer(openFileDialog.FileName);

}

}

}

private void btnPlay_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

if (player != null)

{

player.Play();

}

}

private void btnStop_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

if (player != null)

{

player.Stop();

}

}

}

}

Объяснение кода

-

Инициализация SoundPlayer: Экземпляр SoundPlayer создается при выборе файла через

OpenFileDialog. Это позволяет пользователю выбрать WAV-файл для воспроизведения. -

Воспроизведение музыки: Метод Play класса SoundPlayer используется для воспроизведения звука. Этот метод вызывается при нажатии кнопки «Play».

-

Остановка воспроизведения: Метод Stop используется для остановки воспроизведения. Этот метод вызывается при нажатии кнопки «Stop».

-

OpenFileDialog: Используется для открытия диалогового окна выбора файла, которое позволяет пользователю выбрать WAV-файл для воспроизведения.

Заключение

Этот простой музыкальный плеер демонстрирует базовые возможности класса SoundPlayer в C#. Хотя SoundPlayer поддерживает только WAV-файлы, он предоставляет удобный способ начать работу с аудио в приложениях на платформе .NET. Вы можете расширить это приложение, добавив управление громкостью, плейлисты или поддержку других аудиоформатов с использованием дополнительных библиотек.

Для большего понимания, рекомендую видеокурс Программирование на C# с Нуля до Гуру, в котором подробнее рассказано об особенностях языка C#

-

Создано 26.03.2025 13:28:57

-

Михаил Русаков

Копирование материалов разрешается только с указанием автора (Михаил Русаков) и индексируемой прямой ссылкой на сайт (http://myrusakov.ru)!

Добавляйтесь ко мне в друзья ВКонтакте: http://vk.com/myrusakov.

Если Вы хотите дать оценку мне и моей работе, то напишите её в моей группе: http://vk.com/rusakovmy.

Если Вы не хотите пропустить новые материалы на сайте,

то Вы можете подписаться на обновления: Подписаться на обновления

Если у Вас остались какие-либо вопросы, либо у Вас есть желание высказаться по поводу этой статьи, то Вы можете оставить свой комментарий внизу страницы.

Если Вам понравился сайт, то разместите ссылку на него (у себя на сайте, на форуме, в контакте):

-

Кнопка:

Она выглядит вот так:

-

Текстовая ссылка:

Она выглядит вот так: Как создать свой сайт

- BB-код ссылки для форумов (например, можете поставить её в подписи):

-

Use

System.Media.SoundPlayerto Play a Sound inC# -

Use the

SystemSounds.PlayMethod to Play a Sound inC# -

Embed the Windows Media Player Control in a C# Solution to Play a Sound

-

Add the

Microsoft.VisualBasicReference on the C# Project to Play a Sound

This tutorial will teach you how to play audio files or sounds in Windows Forms using C#. You can’t deny sound’s importance in immersing the audience in game development or technical applications.

C# programming offers four primary ways to implement audio files or sounds to your Windows applications, each useful and practical in unique ways. With such a rich platform as .NET for multiplayer, you can easily create custom sound generators for WAV or other format files.

Furthermore, it is possible to build a byte-based buffer of the wave files (sound files) directly in memory using C# as the WPF cones with excellent built-in multiplayer (audio) support.

The important thing to understand here is the SoundPlayer class which plays sound based on WAV or wave format which makes it not extremely useful instead, the MediaPlayer and MediaElement classes allow the playback of MP3 files.

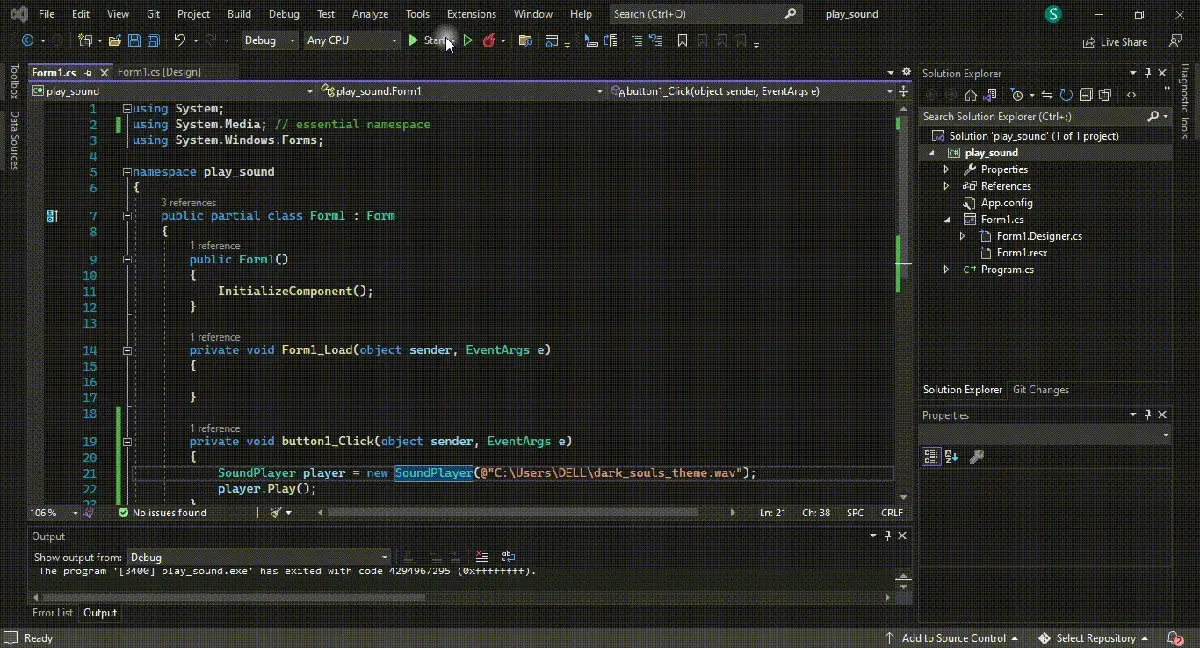

The SoundPlayer class can help play a sound at a given path at run time as it requires the file path, name, and a reference to the System.Media namespace.

You can declare a reference to the System.Media namespace and use SoundPlayer _exp = new SoundPlayer(@"path.wav"); without mentioning the namespace at the object’s declaration.

Afterward, execute it using the Play() method with something like _exp.Play();. Most importantly, file operations like playing a sound should be enclosed within appropriate or suitable structured exception handling blocks for increased efficiency and understanding in case something goes wrong; the path name is malformed, read-only sound file path, null path, and invalid audio file path name can lead to errors and require different exception classes.

using System;

using System.Media; // essential namespace for using `SoundPlayer`

using System.Windows.Forms;

namespace play_sound {

public partial class Form1 : Form {

// Initialize form components

public Form1() {

InitializeComponent();

}

private void Form1_Load(object sender, EventArgs e) {}

private void button1_Click(object sender, EventArgs e) {

// object creation and path selection

SoundPlayer player = new SoundPlayer(@"C:\Users\DELL\dark_souls_theme.wav");

// apply the method to play sound

player.Play();

}

}

}

Output:

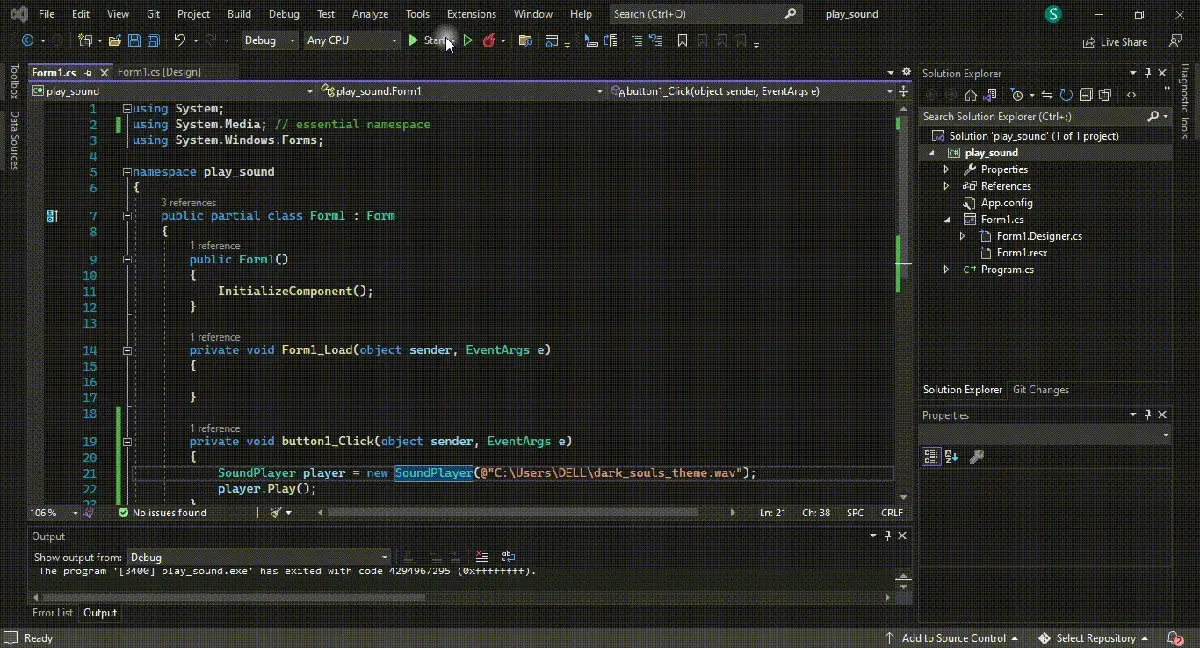

Use the SystemSounds.Play Method to Play a Sound in C#

The functionality (SystemSounds class offers) is one of the simplest ways of implementing sound in your C# applications in addition to its ability to offer different system sounds with a single line of code; SystemSounds.Beep.Play();.

However, there are some limitations to using the SystemSounds class as you can only get access to five different system sounds, including; Asterisk, Beep, Exclamation, Hand, and Question, and in case, you disable system sound in Windows, this method will not work, and all the sounds will be replaced with silence.

On the other hand, it makes it extremely easy to play sounds the same way your Windows does, and it’s always a good choice that your C# application respects the user’s choice of silence.

Declare a reference to the System.Media in your C# project or use something like System.Media.SystemSounds.Asterisk.Play(); to play a sound.

using System;

using System.Media; // essential namespace for `SystemSounds`

using System.Windows.Forms;

namespace play_sound {

public partial class Form1 : Form {

// initialize components

public Form1() {

InitializeComponent();

}

private void Form1_Load(object sender, EventArgs e) {}

private void button1_Click(object sender, EventArgs e) {

SystemSounds.Asterisk.Play(); // you can use other sounds in the place of `Asterisk`

}

}

}

Output:

The Play() method plays the sound asynchronously associated with a set of Windows OS sound-event types. You cannot inherit the SystemSounds class, which provides static methods to access system sounds.

It is a high-level approach that enables C# applications to use different system sounds in typical scenarios that help these applications to seamlessly fit into the Windows environment. It’s possible to customize the sounds in the Sound control panel so that each user profile can override these sounds.

It is possible to add the Windows Media Player control using Microsoft Visual Studio to play a sound in C#. The Windows Media Player is in the VS Toolbox, and to use its functionality in your C# application, first, add its components to your Windows Form.

Install the latest version of Windows Media Player SDK on your system and access it using your VS toolbox by customizing it from the COM components to add the Windows Media Player option. The default name of Windows Media Player in Visual Studio is axWindowsMediaPlayer1, and you can change it to something more rememberable.

Add the Windows Media Player ActiveX control to your C# project and implement it in a button-click event. Furthermore, you can choose two modes: an Independent mode, analogous to the media opened through the Open method, and a Clock mode, a media target corresponding timeline and clock entries in the Timing tree, which controls the playback.

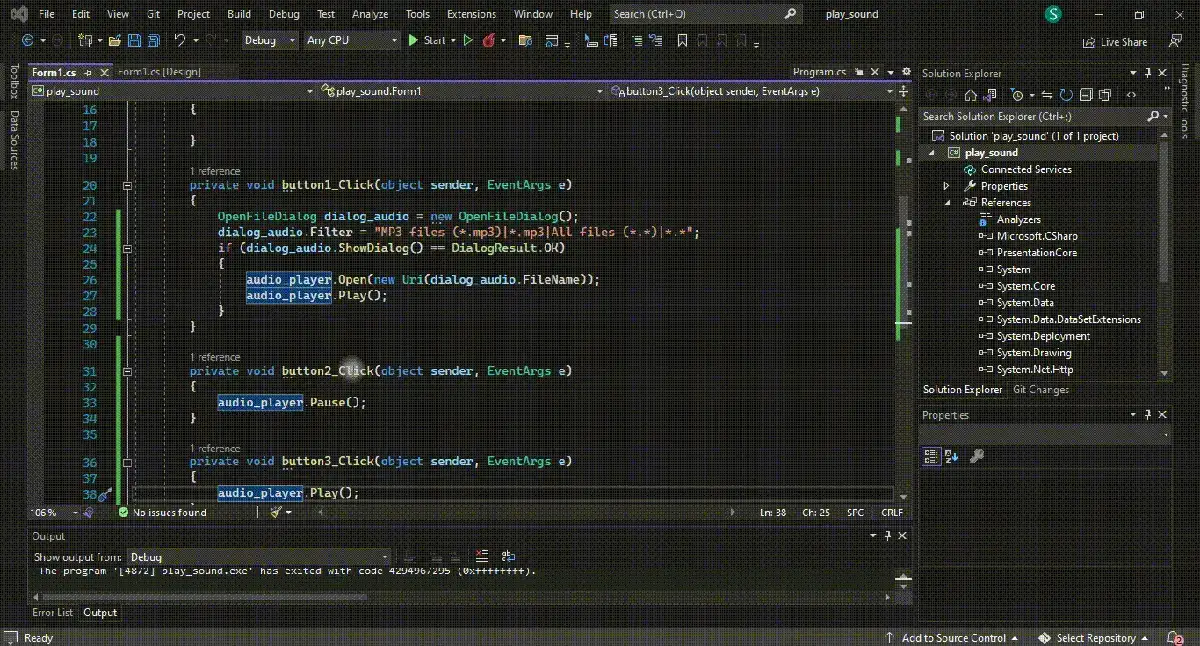

using System;

using System.Windows.Media; // essential namespace

using System.Windows.Forms;

namespace play_sound {

public partial class Form1 : Form {

private MediaPlayer audio_player = new MediaPlayer();

public Form1() {

InitializeComponent();

}

private void Form1_Load(object sender, EventArgs e) {}

private void button1_Click(object sender, EventArgs e) {

OpenFileDialog dialog_audio = new OpenFileDialog();

dialog_audio.Filter = "MP3 files (*.mp3)|*.mp3|All files (*.*)|*.*";

if (dialog_audio.ShowDialog() == DialogResult.OK) {

audio_player.Open(new Uri(dialog_audio.FileName));

audio_player.Play();

}

}

private void button2_Click(object sender, EventArgs e) {

// to pause audio

audio_player.Pause();

}

private void button3_Click(object sender, EventArgs e) {

// to resume the paused audio

audio_player.Play();

}

}

}

Output:

Most importantly, the MediaPlayer class inherits Windows Media Player technology to play audio files and system sound in several modern formats. With its help, you can control the playback process of the sound file mentioned in or carried by the MediaPlayer instance.

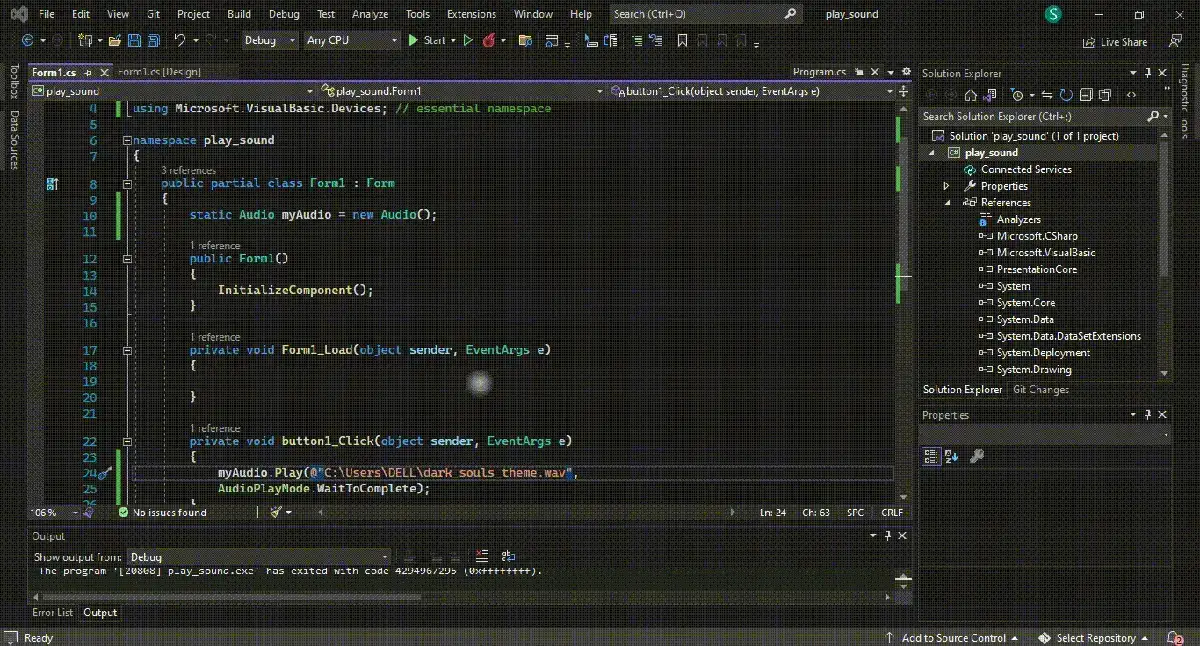

Add the Microsoft.VisualBasic Reference on the C# Project to Play a Sound

The Audio class is incredibly famous in Visual Basic for playing a sound, and you can benefit from it by using it in C# by including the Visual Basic bindings in your application. However, there is a C#-specific version of the Audio class called the SoundPlayer class, but it does not allow easy byte-based buffer building of the wave directly in memory.

Add the Microsoft.VisualBasic reference to your C# project as an initial step and create an object from the Audio class like static Audio my_obj = new Audio(); and add the sound file address like my_exp.Play("m:\\path.wav", AudioPlayMode.WaitToComplete);.

You can customize or set the AudioPlayMode by yourself, which allows you to customize the playback time of the sound.

using System;

using System.Windows.Forms;

using Microsoft.VisualBasic; // essential namespace

using Microsoft.VisualBasic.Devices; // essential namespace

namespace play_sound {

public partial class Form1 : Form {

static Audio audio_player = new Audio();

public Form1() {

InitializeComponent();

}

private void Form1_Load(object sender, EventArgs e) {}

private void button1_Click(object sender, EventArgs e) {

audio_player.Play(@"C:\Users\DELL\dark_souls_theme.wav", AudioPlayMode.WaitToComplete);

}

}

}

Output:

It is a good practice to use the Background or BackgroundLoop tool to resume the other tasks while the audio continues to play in the background.

It is optional; however, you can create custom sounds using nothing more than the C# code by learning the uncompressed WAV file and can create the sound directly in your system’s memory.

This tutorial taught you how to effectively play a sound file in C#.

Enjoying our tutorials? Subscribe to DelftStack on YouTube to support us in creating more high-quality video guides. Subscribe

I’ve been on a spiritual search for a cross-platform solution that allows developers to play and capture audio using .NET 5. It’s a journey filled with many highs and lows, mostly cursing at my screen and ruing the day I ever embarked on this mission. That said, I’ve found a way to play audio using a cross-platform API, even though the approach itself can differ across Windows, macOS, and Linux. This post will show the process we can take to get audio functionality in our .NET console applications.

The Painful Obvious Truth

As a professional for many years, I’ve learned that it’s best to use the platform and avoid abstractions, including database engines, web frameworks, and mobile platforms. While generalizations can increase code reuse, they can also limit functionality to the lowest common denominator. So my journey to find a cross-platform library that was able to play audio cross-platform using .NET purely had doomed from the start.

Through my searches, I found a library called NetCoreAudio. While I was looking through the project’s code, the real solution was painfully obvious.

Use the Operating System and its ability to play audio. –Inner Monologue

Being a macOS user, I could rely on a system utility to play audio from .NET and manage the child process’s lifecycle. NetCoreAudio attempts to create a cross-platform abstraction, but it reduces the native operating system utility’s functionality in the process. Additionally, I found that stopping audio playback was wonky, and the API didn’t take advantage of async/await and CancellationToken constructs.

We can do better!

AFPlay on macOS

Afplay is a macOS command-line utility that allows users to play an audio file via the terminal.

> afplay music.wav -t 5

This utility has many optional flags that can alter the playback of an audio file.

Syntax

afplay [option...] audio_file

Options: (may appear before or after arguments)

-v VOLUME

--volume VOLUME

Set the volume for playback of the file

Apple does not define a value range for this, but it appears to accept

0=silent, 1=normal (default) and then up to 255=Very loud.

The scale is logarithmic and in addition to (not a replacement for) other volume control(s).

-h

--help

Print help.

--leaks

Run leaks analysis.

-t TIME

--time TIME

Play for TIME seconds

>0 and < duration of audio_file.

-r RATE

--rate RATE

Play at playback RATE.

practical limits are about 0.4 (slower) to 3.0 (faster).

-q QUALITY

--rQuality QUALITY

Set the quality used for rate-scaled playback (default is 0 - low quality, 1 - high quality).

-d

--debug

Debug print output.

There’s a lot of great functionality in this utility, and we should take advantage of as much as possible. Be careful with the volume flag; I scared the hell out of my wife and dogs by setting the max value.

Implementing The Afplay C# Wrapper

Folks might feel opposed to wrapping OS utilities, but the .NET library defers many of its cryptographic and networking tasks to the underlying operating system. We should embrace the uniqueness of our platform and utilize its strengths.

In my case, I primarily work on macOS, so I’ll be writing a .NET wrapper for macOS users only. If you need to adapt a wrapper for a specific operating system, I recommend looking at NetCoreAudio and porting its functionality.

Knowing I had to work with processes, I decided to defer process management responsibilities to potentially two .NET OSS projects: SimpleExec and CliWrap. I would recommend you use CliWrap if you need CancellationToken support. Both libraries are excellent abstractions of the Process class.

Let’s take a look at the example project first.

using System;

using System.Threading;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using GhostBusters;

Console.WriteLine("⚡️ peeeew! (Slow lazer)");

await Audio.Play("lazer.wav", new PlaybackOptions { Rate = 0.5, Quality = 1 });

Console.WriteLine("👻 Oooooooo!");

await Audio.Play("ghost.wav");

Console.WriteLine("Don't Cross The Streams!!!!");

// all the ghost busters now

await Task.WhenAll(

Audio.Play("lazer.wav"),

Audio.Play("lazer.wav", new PlaybackOptions { Rate = 0.4, Quality = .5 }),

Audio.Play("lazer.wav", new PlaybackOptions { Rate = 0.8, Quality = 1 }),

Audio.Play("lazer.wav", new PlaybackOptions { Rate = 0.6, Quality = 1 })

);

var cancellation = new CancellationTokenSource();

var keyBoardTask = Task.Run(() => {

Console.WriteLine("Press enter to cancel the birthday song...");

Console.ReadKey();

// Cancel the task

cancellation.Cancel();

});

var happyBirthday = Audio.Play(

"happy-birthday.wav",

new PlaybackOptions(),

cancellation.Token

);

await Task.WhenAny(keyBoardTask, happyBirthday);

if (cancellation.IsCancellationRequested) {

Console.WriteLine("🥳 Someone's a party pooper...");

}

We can call the Audio class’ Play method and pass all of the utility parameters accepted by afplay. Additionally, we are using async/await syntax to ensure that an audio file only moves on to the next line was the file has completed playing. Finally, we can pass a CancellationToken to our Play method to abruptly stop playing the audio file. The utility has no pause and resume functionality, which I wish it did.

Let’s take a look at the implementation.

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.IO;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using CliWrap;

namespace GhostBusters

{

public static class Audio

{

public static async Task<PlaybackResult> Play(

string filename,

PlaybackOptions options = null,

CancellationToken token = default

)

{

options??= new PlaybackOptions();

var arguments = options.GetArguments();

// add filename

arguments.Add(filename);

var sb = new StringBuilder();

var command =

await Cli

.Wrap("afplay")

.WithArguments(string.Join(" ", arguments))

.WithStandardOutputPipe(PipeTarget.ToStringBuilder(sb))

.ExecuteAsync(token);

var output = sb.ToString();

return new PlaybackResult(output);

}

}

public record PlaybackResult

{

public PlaybackResult(string result)

{

if (result == null)

return;

var reader = new StringReader(result);

Filename = reader.ReadLine()?.Split(':')[1].Trim();

var line = reader.ReadLine();

Format = line?.Substring(line.LastIndexOf(':') + 1).Trim();

var sizes = reader.ReadLine()?.Split(',');

if (sizes != null)

{

BufferByteSize = int.Parse(sizes[0].Split(':').LastOrDefault() ?? "0");

NumberOfPacketsToRead = int.Parse(sizes[1].Split(':').LastOrDefault() ?? "0");

}

}

public string Filename { get; }

public string Format { get; }

public int BufferByteSize { get; }

public int NumberOfPacketsToRead { get; }

}

public class PlaybackOptions

{

/// <summary>

/// Set the volume for playback of the file

/// Apple does not define a value range for this, but it appears to accept

/// 0=silent, 1=normal (default) and then up to 255=Very loud.

/// The scale is logarithmic and in addition to (not a replacement for) other volume control(s).

/// </summary>

public int? Volume { get; init; }

/// <summary>

/// Play for Time in Seconds

/// </summary>

public int? Time { get; init; }

/// <summary>

/// Play at playback RATE.

/// practical limits are about 0.4 (slower) to 3.0 (faster).

/// </summary>

public double? Rate { get; init; }

/// <summary>

/// Set the quality used for rate-scaled playback (default is 0 - low quality, 1 - high quality).

/// </summary>

public double? Quality { get; init; }

internal List<string> GetArguments()

{

var arguments = new List<string> { "-d" };

if (Volume.HasValue) {

arguments.Add($"-v {Volume}");

}

if (Time.HasValue) {

arguments.Add($"-t {Time}");

}

if (Rate.HasValue) {

arguments.Add($"-r {Rate}");

}

if (Quality.HasValue) {

arguments.Add($"-q {Quality}");

}

return arguments;

}

}

}

We have a fully-featured C# wrapper around a native audio player in just a few lines of code. CliWrap and macOS are doing much of the heavy lifting here.

Your browser does not support the video tag.

Users of macOS can clone the sample GitHub repository.

Conclusion

While it would be nice to have a pure C# solution that works regardless of the operating system, it’s impossible to achieve that goal (as far as I know). Given each OS has its own set of permissions and access to hardware, this solution seems to be the best I can muster. NetCoreAudio is an excellent library, and folks should look at it if they need a cross-platform solution. Still, folks should also consider writing their own wrapper using CliWrap to get better async/await support.

Thanks for reading, and I hope you found this post helpful. Please leave a comment below.

Hearing is one of the few basic senses that we humans have along with the other our abilities to see, smell, taste and touch. If we couldn’t hear, the world as we know it would be less interesting and colorful to us. It would be a total silence — a scary thing, even to imagine. And speaking makes our life so much fun, because what else can be better than talking to our friends and family? Also, we’re able to listen to our favorite music wherever we are, thanks to computers and headphones. With the help of tiny microphones integrated into our phones and laptops we are now able to talk to the people around the world from any place with an Internet connection. But computer hardware alone isn’t enough — it is computer software that really defines the way how and when the hardware should operate. Operating Systems provide the means for that to the apps that want to use computer’s audio capabilities. In real use-cases audio data usually goes the long way from one end to another, being transformed and (un)compressed on-the-fly, attenuated, filtered, and so on. But in the end it all comes down to just 2 basic processes: playing the sound or recording it.

Today we’re going to discuss how to make use of the API that popular OS provide: this is an essential knowledge if you want to create an app yourself which works with audio I/O. But there’s just one problem standing on our way: there is no single API that all OS support. In fact, there are completely different API, different approaches, slightly different logic. We could just use some library which solves all those problems for us, but in that case we won’t understand what’s really going on under the hood — what’s the point? But humans are built the way that we sometimes want to dig a little bit deeper, to learn a little bit more than what just lies on the surface. That’s why we’re going to learn the API that OS provide by default: ALSA (Linux), PulseAudio (Linux), WASAPI (Windows), OSS (FreeBSD), CoreAudio (macOS).

Although I try to explain every detail that I think is important, these API are so complex that in any case you need to find the official documentation which explains all functions, identificators, parameters, etc, in much more detail. Going through this tutorial doesn’t mean you don’t need to read official docs — you have to, or you’ll end up with an incomplete understanding of the code you write.

All sample code for this guide is available here: https://github.com/stsaz/audio-api-quick-start-guide. I recommend that while reading this tutorial you should have an example file opened in front of you so that you better understand the purpose of each code statement in global context. When you’re ready for slightly more advanced usage of audio API, you can analyze the code of ffaudio library: https://github.com/stsaz/ffaudio.

Contents:

-

Overview

-

Audio Data Representation

-

Linux and ALSA

-

ALSA: Enumerating Devices

-

ALSA: Opening Audio Buffer

-

ALSA: Recording Audio

-

ALSA: Playing Audio

-

ALSA: Draining

-

ALSA: Error Checking

-

-

Linux and PulseAudio

-

PulseAudio: Enumerating Devices

-

PulseAudio: Opening Audio Buffer

-

PulseAudio: Recording Audio

-

PulseAudio: Playing Audio

-

PulseAudio: Draining

-

-

Windows and WASAPI

-

WASAPI: Enumerating Devices

-

WASAPI: Opening Audio Buffer in Shared Mode

-

WASAPI: Recording Audio in Shared Mode

-

WASAPI: Playing Audio in Shared Mode

-

WASAPI: Draining in Shared Mode

-

WASAPI: Error Reporting

-

-

FreeBSD and OSS

-

OSS: Enumerating Devices

-

OSS: Opening Audio Buffer

-

OSS: Recording Audio

-

OSS: Playing Audio

-

OSS: Draining

-

OSS: Error Reporting

-

-

macOS and CoreAudio

-

CoreAudio: Enumerating Devices

-

CoreAudio: Opening Audio Buffer

-

CoreAudio: Recording Audio

-

CoreAudio: Playing Audio

-

CoreAudio: Draining

-

-

Final Results

Overview

First, I’m gonna describe how to work with audio devices in general, without any API specifics.

Step 1. It all starts with enumerating the available audio devices. There are 2 types of devices OS have: a playback device, in which we write audio data, or a capture device, from which we read audio data. Every device has its own unique ID, name and other properties. Every app can access this data to select the best device for its need or to show all devices to its user so he can select the one he likes manually. However, most of the time we don’t need to select a specific device, but rather just use the default device. In this case we don’t need to enumerate devices and we won’t even need to retrieve any properties.

Note that there can be a registered device in the system but unavailable, for example when the user disabled it in system settings. If we perform all necessary error checks when writing our code, we won’t normally see any disabled devices.

Sometimes we can retrieve the list of all supported audio formats for a particular device, but I wouldn’t rely on this info very much — it’s not cross-platform, after all. Instead, it’s better to try to assign an audio buffer to this device and see if the audio format is supported for sure.

Step 2. After we have determined what device we want to use, we continue with creating an audio buffer and assigning it to device. At this point we must know the audio format we’d like to use: sample format (e.g. signed integer), sample width (e.g. 16 bit), sample rate (e.g. 48000 Hz) and the number of channels (e.g. 2 for stereo).

Sample format is either signed integer, unsigned integer or a floating point number. Some audio drivers support all integers and floats, while some may support just 16-bit signed integers and nothing else. This doesn’t always mean that the device works with them natively — it’s possible that audio device software converts samples internally.

Sample width is the size of each sample, 16 bit is the standard for CD Audio quality, but it’s not the best choice for audio processing use-cases because it can easily produce artifacts (although, it’s unlikely that we can really tell the difference). 24 bit is much better and it’s supported by many audio devices. But nevertheless, the professional sound apps don’t give any chance to sound artifacts: they use 64-bit float samples internally when performing mixing operations and other types of filtering.

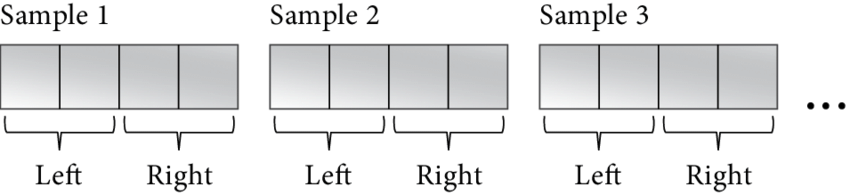

Sample rate is the number of samples necessary to get 1 whole second of audio data. The most popular rates are 44.1KHz and 48KHz, but audiophiles may argue that 96KHz sample rate is the best. Usually, audio devices can work with rates up to 192KHz, but I really don’t believe that anybody can hear any difference between 48KHz and higher values. Note that sample rate is the number of samples per second for one channel only. So in fact for 16bit 48KHz stereo stream the number of bytes we have to process is 2 * 48000 * 2.

0 sec 1 sec

| (Sample 0) ... (Sample 47999) |

| short[L] ... short[L] |

| short[R] ... short[R] |Sometimes samples are called frames, similar to video frames. An audio sample/frame is a stack of numerical values which together form the audio signal strength for each hardware device channel for the same point in time. Note, however, that some official docs don’t agree with me on this: they specifically define that a sample is just 1 numerical value, while the frame is a set of those values for all channels. Why don’t they call sample rate a frame rate then? Please take a look at the diagram above once again. There, the sample width (column width) is still 16bit, no matter how many channels (rows below) we have. Sample format (which is a signed integer in our case) always stays the same too. Sample rate is the number of columns for 1 second of audio, no matter how many channels we have. Therefore, my own logic tells me the definition of an audio sample to me (no matter how others may define it), but your logic may be different — that’s totally fine.

Sample size (or frame size) is another property that you will often use while working with digital audio. This is just a constant value to conveniently convert the number of bytes to the number of audio samples and vice versa:

int sample_size = sample_width/8 * channels;

int bytes_in_buffer = samples_in_buffer * sample_size;Of course, we can also set more parameters for our audio buffer, such as the length of our buffer (in milliseconds or in bytes) which is the main property for controlling sound latency. But keep in mind that every device has its own limits for this parameter: we can’t set the length too low when device just doesn’t support it. I think that 250ms is a fine starting point for most applications, but some real-time apps require the minimum possible latency at the cost of higher CPU usage — it all depends on your particular use-case.

When opening an audio device we should always be ready if the API we use returns with a «bad format» error which means that the audio format we chose isn’t supported by the underlying software or by physical device itself. In this case we should select a more suitable format and recreate the buffer.

Note that one physical device can be opened only once, we can’t attach 2 or more audio buffers to the same device — what a mess it would be otherwise, right? But in this case we need to solve a problem with having multiple audio apps that want to play some audio in parallel via the single device. Windows solves this problem in WASAPI by introducing 2 different modes: shared and exclusive. In shared mode we attach our audio buffers to a virtual device, which mixes all streams from different apps together, applies some filtering such as sound attenuation and then passes the data to a physical device. And PulseAudio on Linux works the same way on top of ALSA. Of course, the downside is that the shared mode has to have a higher latency and a higher CPU usage. On the other hand, in exclusive mode we have almost direct connection to audio device driver meaning that we can achieve the maximum sound quality and minimum latency, but no other app will be able to use this device while we’re using it.

Step 3. After we have prepared and configured an audio buffer, we can start using it: writing data to it for playback or reading data from it to record audio. Audio buffer is in fact a circular buffer, where reading and writing operations are performed infinitely in circle.

But there is one problem: CPU must be in synchronization with the audio device when performing I/O on the same memory buffer. If not, CPU will work at its full speed and run over the audio buffer some million times while the audio device only finishes its first turn. Therefore, CPU must always wait for the audio device to slowly do its work. Then, after some time, CPU wakes up for a short time period to get some more audio data from the device (when recording) or to feed some more data to the device (in playback mode), and then CPU should continue sleeping. Note that this is where the audio buffer length parameter comes into play: the less the buffer size — the more times CPU must wake up to perform its work. A circular buffer can be in 3 different states: empty, half-full and full. And we need to understand how to properly handle all those states in our code.

Empty buffer while recording means that there are no audio samples available to us at the moment. We must wait until audio device puts something new into it.

Empty buffer while playing means that we are free to write audio data into the buffer at any time. However, if the audio device is running and it comes to this point when there’s no more data available for it to read, it means that we have failed to keep up with it, this situation is called buffer underrun. If we are in this state, we should pause the device, fill the audio buffer and then resume the normal operation.

Half-full buffer while recording means that there are some audio samples inside the buffer, but it’s not yet completely full. We should process the available data as soon as we can and mark this data region as read (or useless) so that the next time we won’t see this data as available.

Half-full buffer for playback streams means that we can put some more data into it.

Full buffer for recording streams means that we are falling behind the audio device to read the available data. Audio device has filled the buffer completely and there’s no more room for new data. This state is called buffer overrun. In this case we must reset the buffer and resume (unpause) the device to continue normally.

Full buffer for playback streams is a normal situation and we should just wait until some free space is available.

A few words about how the waiting process is performed. Some API provide the means for us to subscribe to notifications to achieve I/O with the least possible latency. For example, ALSA can send SIGIO signal to our process after it has written some data into audio recording buffer. WASAPI in exclusive mode can notify us via a Windows kernel event object. However, for apps that don’t require so much accuracy we can simply use our own timers, or we can just block our process with functions like usleep/Sleep. When using these methods we just have to make sure that we sleep not more than half of our audio buffer length, .e.g. for 500ms buffer we may set the timer to 250ms and perform I/O 2 times per each buffer rotation. Of course you understand that we can’t do it reliably for very small buffers, because even a slight delay can cause audio stutter. Anyway, in this tutorial we don’t need high accuracy, but we need small code that is easier to understand.

Step 4. For playback buffers there’s one more thing. After we have completed writing all our data into audio buffer, we must still wait for it to process the data. In other words, we should drain the buffer. Sometimes we should manually add silence to the buffer, otherwise it could play a chunk of some old invalid data, resulting in audio artifacts. Then, after we see that the whole buffer has become empty, we can stop the device and close the buffer.

Also, keep in mind that during the normal operation these problems may arise:

-

The physical audio device can be switched off by user and become unavailable for us.

-

The virtual audio device could be reconfigured by user and require us to reopen and reconfigure audio buffers.

-

CPU was too busy performing some other operations (for another app or system service) resulting in buffer overrun/underrun condition.

Careful programmer must always check for all possible scenarios, check all return codes from API functions that we call and handle them or show an error message to user. I don’t do it in my sample code just because this tutorial is for you to understand an audio API. And this purpose is fulfilled with the shortest possible code for you to read — error checking everywhere will make the things worse in this case.

Of course, after we are done, we must close the handlers to audio buffers and devices, free allocated memory regions. But we don’t wanna do that in case we just want to play another audio file, for example. Preparing a new audio buffer can take a lot of time, so always try to reuse it when you can.

Audio Data Representation

Now let’s talk about how audio data is actually organized and how to analyze it. There are 2 types of audio buffers: interleaved and non-interleaved. Interleaved buffer is a single contiguous memory region where the sets of audio samples go one by one. This is how it looks like for 16bit stereo audio:

short[0][L]

short[0][R]

short[1][L]

short[1][R]

...

Here, 0 and 1 are the sample indexes, and L and R are the channels. For example, how we can read the values for both channels for sample #9 is we take the sample index and multiply it by the number of channels:

short *samples = (short*)buffer;

short sample_9_left = samples[9*2];

short sample_9_right = samples[9*2 + 1];These 16-bit signed values are the signal strength where 0 is silence. But the signal strength is usually measured in dB values. Here’s how we can convert our integer values to dB:

short sample = ...;

double gain = (double)sample * (1 / 32768.0);

double db = log10(gain) * 20;Here we first convert integer to a float number — this is gain value where 0.0 is silence and +/-1.0 — max signal. Then, using gain = 10 ^ (db / 20) formula we convert the gain into dB value. If we want to do an opposite conversion, we may use this code:

#include <emmintrin.h> // SSE2 functions. All AMD64 CPU support them.

double db = ...;

double gain = pow(10, db / 20);

double d = gain * 32768.0;

short sample;

if (d < -32768.0)

sample = -0x8000;

else if (d > 32768.0 - 1)

sample = 0x7fff;

else

sample = _mm_cvtsd_si32(_mm_load_sd(&d));I’m not an expert in audio math, I’m just showing you how I do it, but you may find a better solution.

The most popular audio codecs and the most audio API use interleaved audio data format.

Non-interleaved buffer is an array of (potentially) different memory regions, one for each channel:

L -> {

short[0][L]

short[1][L]

...

}

R -> {

short[0][R]

short[1][R]

...

}For example, the mainstream Vorbis and FLAC audio codecs use this format. As you can see, it’s very easy to operate on samples within a single channel in non-interleaved buffers. For example, swapping left and right channels would take just a couple of CPU cycles to swap the pointers.

I think we’ve had enough theory and we’re ready for some real code with a real audio API.

Linux and ALSA

ALSA is Linux’s default audio subsystem, so let’s start with it. ALSA consists of 2 parts: audio drivers that live inside the kernel and user API which provides universal access to the drivers. We’re going to learn user mode ALSA API — it’s the lowest level for accessing sound hardware in user mode.

First, we must install development package, which is libalsa-devel for Fedora. Now we can include it in our code:

#include <alsa/asoundlib.h>And when linking our binaries we add -lalsa flag.

ALSA: Enumerating Devices

First, iterate over all sound cards available in the system, until we get a -1 index:

int icard = -1;

for (;;) {

snd_card_next(&icard);

if (icard == -1)

break;

...

}For each sound card index we prepare a NULL-terminated string, e.g. hw:0, which is a unique ID of this sound card. We receive the sound card handler from snd_ctl_open(), which we later close with snd_ctl_close().

char scard[32];

snprintf(scard, sizeof(scard), "hw:%u", icard);

snd_ctl_t *sctl = NULL;

snd_ctl_open(&sctl, scard, 0);

...

snd_ctl_close(sctl);For each sound card we walk through all its devices until we get -1 index:

int idev = -1;

for (;;) {

if (0 != snd_ctl_pcm_next_device(sctl, &idev)

|| idev == -1)

break;

...

}Now prepare a NULL-terminated string, e.g. plughw:0,0, which is the device ID we can later use when assigning an audio buffer. plughw: prefix means that ALSA will try to apply some audio conversion when necessary. If we want to use hardware device directly, we should use hw: prefix instead. For default device we may use plughw:0,0 string, but in theory it can be unavailable — you should provide a way for the user to select a specific device.

char device_id[64];

snprintf(device_id, sizeof(device_id), "plughw:%u,%u", icard, idev);ALSA: Opening Audio Buffer

Now that we know the device ID, we can assign a new audio buffer to it with snd_pcm_open(). Note that we won’t be able to open the same ALSA device twice. And if this device is used by system PulseAudio process, no other app in the system will be able to use audio while we’re holding it.

snd_pcm_t *pcm;

const char *device_id = "plughw:0,0";

int mode = (playback) ? SND_PCM_STREAM_PLAYBACK : SND_PCM_STREAM_CAPTURE;

snd_pcm_open(&pcm, device_id, mode, 0);

...

snd_pcm_close(pcm);Next, set the parameters for our buffer. Here we tell ALSA that we want to use mmap-style functions to get direct access to its buffers and that we want an interleaved buffer. Then, we set audio format and the buffer length. Note that ALSA updates some values for us if the values we supplied are not supported by device. However, if sample format isn’t supported, we have to find the right value manually by probing with snd_pcm_hw_params_get_format_mask()/snd_pcm_format_mask_test(). In real life you should check if your higher-level code supports this new configuration.

snd_pcm_hw_params_t *params;

snd_pcm_hw_params_alloca(¶ms);

snd_pcm_hw_params_any(pcm, params);

int access = SND_PCM_ACCESS_MMAP_INTERLEAVED;

snd_pcm_hw_params_set_access(pcm, params, access);

int format = SND_PCM_FORMAT_S16_LE;

snd_pcm_hw_params_set_format(pcm, params, format);

u_int channels = 2;

snd_pcm_hw_params_set_channels_near(pcm, params, &channels);

u_int sample_rate = 48000;

snd_pcm_hw_params_set_rate_near(pcm, params, &sample_rate, 0);

u_int buffer_length_usec = 500 * 1000;

snd_pcm_hw_params_set_buffer_time_near(pcm, params, &buffer_length_usec, NULL);

snd_pcm_hw_params(pcm, params);Finally, we need to remember the frame size and the whole buffer size (in bytes).

int frame_size = (16/8) * channels;

int buf_size = sample_rate * (16/8) * channels * buffer_length_usec / 1000000;ALSA: Recording Audio

To start recording we call snd_pcm_start():

snd_pcm_start(pcm);During normal operation we ask ALSA for some new audio data with snd_pcm_mmap_begin() which returns the buffer, offset to the valid region and the number of valid frames. For this function to work correctly we should first call snd_pcm_avail_update() which updates the buffer’s internal pointers. After we have processed the data, we must dispose of it with snd_pcm_mmap_commit().

for (;;) {

snd_pcm_avail_update(pcm);

const snd_pcm_channel_area_t *areas;

snd_pcm_uframes_t off;

snd_pcm_uframes_t frames = buf_size / frame_size;

snd_pcm_mmap_begin(pcm, &areas, &off, &frames);

...

snd_pcm_mmap_commit(pcm, off, frames);

}When we get 0 frames available, it means that the buffer is empty. Start the recording stream if necessary, then wait for some more data. I use 100ms interval, but actually it should be computed using the real buffer size.

if (frames == 0) {

int period_ms = 100;

usleep(period_ms*1000);

continue;

}After we’ve got some data, we get the pointer to the actual interleaved data and the number of available bytes in this region:

const void *data = (char*)areas[0].addr + off * areas[0].step/8;

int n = frames * frame_size;ALSA: Playing Audio

Writing audio is almost the same as reading it. We get the buffer region by snd_pcm_mmap_begin(), copy our data to it and then mark it as complete with snd_pcm_mmap_commit(). When the buffer is full, we receive 0 available free frames. In this case we start the playback stream for the first time and start waiting until some free space is available in the buffer.

if (frames == 0) {

if (SND_PCM_STATE_RUNNING != snd_pcm_state(pcm))

snd_pcm_start(pcm);

int period_ms = 100;

usleep(period_ms*1000);

continue;

}ALSA: Draining

To drain playback buffer we don’t need to do anything special. First, we check whether there is still some data in buffer and if so, wait until the buffer is completely empty.

for (;;) {

if (0 >= snd_pcm_avail_update(pcm))

break;

if (SND_PCM_STATE_RUNNING != snd_pcm_state(pcm))

snd_pcm_start(pcm);

int period_ms = 100;

usleep(period_ms*1000);

}But why do we always check the state of our buffer and then call snd_pcm_start() if necessary? It’s because ALSA never starts streaming automatically. We need to start it initially after the buffer is full, and we need to start it every time an error such as buffer overrun occurs. We also need to start it in case we haven’t filled the buffer completely.

ALSA: Error Checking

Most of the ALSA functions we use here return integer result codes. They return 0 on success and non-zero error code on failure. To translate an error code to a user-friendly error message we can use snd_strerror() function. I also recommend storing the name of the function that returned with an error so that the user has complete information about what went wrong exactly.

But there’s more. During normal operation while recording or playing audio we should handle buffer overrun/underrun cases. Here’s how to do it. First, check if the error code is -EPIPE. Then, call snd_pcm_prepare() to reset the buffer. If it fails, then we can’t continue normal operation, it’s a fatal error. If it completes successfully, we continue normal operation as if there was no buffer overrun. Why can’t ALSA just handle this case internally? To give us more control over our program. For example, some app in this case must notify the user that an audio data chunk was lost.

if (err == -EPIPE)

assert(0 == snd_pcm_prepare(pcm));Next case when we need special error handling is after we have called snd_pcm_mmap_commit() function. The problem is that even if it returns some data and not an error code, we still need to check whether all data is processed. If not, we set -EPIPE error code ourselves and we can then handle it with the same code as shown above.

err = snd_pcm_mmap_commit(pcm, off, frames);

if (err >= 0 && (snd_pcm_uframes_t)err != frames)

err = -EPIPE;Next, the functions may return -ESTRPIPE error code which means that for some reason the device we’re currently using has been temporarily stopped or paused. If it happens, we should wait until the device comes online again, periodically checking its state with snd_pcm_resume(). And then we call snd_pcm_prepare() to reset the buffer and continue as usual.

if (err == -ESTRPIPE) {

while (-EAGAIN == snd_pcm_resume(pcm)) {

int period_ms = 100;

usleep(period_ms*1000);

}

snd_pcm_prepare(pcm);

}Don’t forget that after handling those errors we need to call snd_pcm_start() to start the buffer. For recording streams we do it immediately, and for playback streams we do it when the buffer is full.

Linux and PulseAudio

PulseAudio works on top of ALSA, it can’t substitute ALSA — it’s just an audio layer with several useful features for graphical multi-app environment, e.g. sound mixing, conversion, rerouting, playing audio notifications. Therefore, unlike ALSA, PulseAudio can share a single audio device between multiple apps — I think this is the main reason why it’s useful.

Note that on Fedora PulseAudio is not the default audio layer anymore, it’s replaced with PipeWire with yet another audio API (though PulseAudio apps will continue to work via the PipeWire-PulseAudio layer). But until PipeWire isn’t the default choice on other popular Linux distributions, PulseAudio is more useful overall.

First, we must install development package, which is libpulse-devel for Fedora. Now we can include it in our code:

#include <pulse/pulseaudio.h>And when linking our binaries we add -lpulse flag.

A couple words about how PulseAudio is different from others. PulseAudio has a client-server design which means we don’t operate on an audio device directly but just issue commands to PulseAudio server and receive the response from it. Thus, we always start with connecting to PulseAudio server. We have to implement somewhat complex logic to do it, because the interaction between us and the server is asynchronous: we have to send a command to server and then wait for it to process our command and receive the result, all via a socket (UNIX) connection. Of course, this communication takes some time, and we can do some other stuff while waiting for the server’s response. But with our sample code here we won’t be that clever: we will just wait for responses synchronously which is easier to understand.

We begin by creating a separate thread which will process socket I/O operations for us. Don’t forget to stop this thread and close its handlers after we’re done with PulseAudio.

pa_threaded_mainloop *mloop = pa_threaded_mainloop_new();

pa_threaded_mainloop_start(mloop);

...

pa_threaded_mainloop_stop(mloop);

pa_threaded_mainloop_free(mloop);The first thing to remember when using PulseAudio is that we must perform all operations while holding the internal lock for this I/O thread. «Lock the thread», perform necessary calls to PA objects, and then «unlock the thread». Failing to properly lock the thread may at any point result in race condition. This lock is recursive, meaning that it’s safe to lock it several time from the same thread. Just call the unlocking function the same number of times. However, I don’t see how the lock recursiveness is useful in real life. Recursive locks usually mean that we have a bad architecture and they can cause difficult to find problems — I never advise to use this feature.

pa_threaded_mainloop_lock(mloop);

...

pa_threaded_mainloop_unlock(mloop);Now begin connection to PA server. Note that pa_context_connect() function usually returns immediately even if the connection isn’t yet established. We’ll receive the result of connection later in a callback function we set via pa_context_set_state_callback(). Don’t forget to disconnect from the server when we’re done.

pa_mainloop_api *mlapi = pa_threaded_mainloop_get_api(mloop);

pa_context *ctx = pa_context_new_with_proplist(mlapi, "My App", NULL);

void *udata = NULL;

pa_context_set_state_callback(ctx, on_state_change, udata);

pa_context_connect(ctx, NULL, 0, NULL);

...

pa_context_disconnect(ctx);

pa_context_unref(ctx);After we’ve issued the connection command we have nothing more to do except waiting for the result. We ask for the connection status, and if it’s not yet ready, we call pa_threaded_mainloop_wait() which blocks our thread until a signal is received.

while (PA_CONTEXT_READY != pa_context_get_state(ctx)) {

pa_threaded_mainloop_wait(mloop);

}And here’s how our on-state-change callback function looks like. Nothing clever: we just signal the our thread to exit from pa_threaded_mainloop_wait() where we’re currently hanging. Note that this function is called not from our own thread (it still keeps hanging), but from the I/O thread we started previously with pa_threaded_mainloop_start(). As a general rule, try to keep the code in these callback functions as small as possible. Your function is called, you receive the result and send a signal to your thread — that should be enough.

void on_state_change(pa_context *c, void *userdata)

{

pa_threaded_mainloop_signal(mloop, 0);

}I hope this call-stack diagram makes this PA server connection logic a little bit clearer for you:

[Our Thread]

|- pa_threaded_mainloop_start()

| [PA I/O Thread]

|- pa_context_connect() |

|- pa_threaded_mainloop_wait() |

| |- on_state_change()

| |- pa_threaded_mainloop_signal()

[pa_threaded_mainloop_wait() returns]The same logic applies to handling all operations results with our callback functions.

PulseAudio: Enumerating Devices

After the connection to PA server is established, we proceed by listing the available devices. We create a new operation with a callback function. We can also pass some pointer to our callback function, but I just use NULL value. Don’t forget to release the pointer after the operation is complete. And of course, this code should be executed only while holding the mainloop thread lock.

pa_operation *op;

void *udata = NULL;

if (playback)

op = pa_context_get_sink_info_list(ctx, on_dev_sink, udata);

else

op = pa_context_get_source_info_list(ctx, on_dev_source, udata);

...

pa_operation_unref(op);Now wait until the operation is complete.

for (;;) {

int r = pa_operation_get_state(op);

if (r == PA_OPERATION_DONE || r == PA_OPERATION_CANCELLED)

break;

pa_threaded_mainloop_wait(mloop);

}While we’re at it, the I/O thread is receiving data from server and performs several successful calls to our callback function where we can access all properties for each available device. When an error occurrs or when there are no more devices, eol parameter is set to a non-zero value. When this happens we just send the signal to our thread. The function for listing playback devices looks this way:

void on_dev_sink(pa_context *c, const pa_sink_info *info, int eol, void *udata)

{

if (eol != 0) {

pa_threaded_mainloop_signal(mloop, 0);

return;

}

const char *device_id = info->name;

}And the function for listing recording devices looks similar:

void on_dev_source(pa_context *c, const pa_source_info *info, int eol, void *udata)The value of udata is the value we set while calling pa_context_get_*_info_list(). In our code they always NULL because my mloop variable is global and we don’t need anything else.

PulseAudio: Opening Audio Buffer

We create a new audio buffer with pa_stream_new() passing our connection context to it, the name of our application and the sound format we want to use.

pa_sample_spec spec;

spec.format = PA_SAMPLE_S16LE;

spec.rate = 48000;

spec.channels = 2;

pa_stream *stm = pa_stream_new(ctx, "My App", &spec, NULL);

...

pa_stream_unref(stm);Next, we attach our buffer to device with pa_stream_connect_*(). We set buffer length in pa_buffer_attr::tlength in bytes, and we leave all other parameters as default (setting them to -1). We also assign with pa_stream_set_*_callback() our callback function which will be called every time audio I/O is complete. We can use device_id value we obtained while enumerating devices or we can use NULL for default device.

pa_buffer_attr attr;

memset(&attr, 0xff, sizeof(attr));

int buffer_length_msec = 500;

attr.tlength = spec.rate * 16/8 * spec.channels * buffer_length_msec / 1000;For recording streams we do:

void *udata = NULL;

pa_stream_set_read_callback(stm, on_io_complete, udata);

const char *device_id = ...;

pa_stream_connect_record(stm, device_id, &attr, 0);

...

pa_stream_disconnect(stm);And for playback streams:

void *udata = NULL;

pa_stream_set_write_callback(stm, on_io_complete, udata);

const char *device_id = ...;

pa_stream_connect_playback(stm, device_id, &attr, 0, NULL, NULL);

...

pa_stream_disconnect(stm);As usual, we have to wait until our operation is complete. We read the current state of our buffer with pa_stream_get_state(). PA_STREAM_READY means that recording is started successfully and we can proceed with normal operation. PA_STREAM_FAILED means an error occurred.

for (;;) {

int r = pa_stream_get_state(stm);

if (r == PA_STREAM_READY)

break;

else if (r == PA_STREAM_FAILED)

error

pa_threaded_mainloop_wait(mloop);

}While we’re hanging inside pa_threaded_mainloop_wait() our callback function on_io_complete() will be called at some point inside I/O thread. Now we just send a signal to our main thread.

void on_io_complete(pa_stream *s, size_t nbytes, void *udata)

{

pa_threaded_mainloop_signal(mloop, 0);

}PulseAudio: Recording Audio

We obtain the data region with audio samples from PulseAudio with pa_stream_peek() and after we have processed it, we discard this data with pa_stream_drop().

for (;;) {

const void *data;

size_t n;

pa_stream_peek(stm, &data, &n);

if (n == 0) {

// Buffer is empty. Process more events

pa_threaded_mainloop_wait(mloop);

continue;

} else if (data == NULL && n != 0) {

// Buffer overrun occurred

} else {

...

}

pa_stream_drop(stm);

}pa_stream_peek() returns 0 samples when buffer is empty. In this case we don’t need to call pa_stream_drop() and we should wait until more data arrives. When buffer overrun occurs we have data=NULL. This is just a notification to us and we can proceed by calling pa_stream_drop() and then pa_stream_peek() again.

PulseAudio: Playing Audio

When we write data to an audio device, we first must get the amount of free space in the audio buffer with pa_stream_writable_size(). It returns 0 when the buffer is full, and we must wait until some free space is available and then try again.

size_t n = pa_stream_writable_size(stm);

if (n == 0) {

pa_threaded_mainloop_wait(mloop);

continue;

}We get the buffer region where into we can copy audio samples with pa_stream_begin_write(). After we’ve filled the buffer, we call pa_stream_write() to release this memory region.

void *buf;

pa_stream_begin_write(stm, &buf, &n);

...

pa_stream_write(stm, buf, n, NULL, 0, PA_SEEK_RELATIVE);PulseAudio: Draining

To drain the buffer we create a drain operation with pa_stream_drain() and pass our callback function to it which will be called when draining is complete.

void *udata = NULL;

pa_operation *op = pa_stream_drain(stm, on_op_complete, udata);

...

pa_operation_unref(op);Now wait until our callback function signals us.

for (;;) {

int r = pa_operation_get_state(op);

if (r == PA_OPERATION_DONE || r == PA_OPERATION_CANCELLED)

break;

pa_threaded_mainloop_wait(mloop);

}Here’s how our callback function looks like:

void on_op_complete(pa_stream *s, int success, void *udata)

{

pa_threaded_mainloop_signal(mloop, 0);

}Windows and WASAPI

WASAPI is default sound subsystem starting with Windows Vista. It’s a successor to DirectSound API which we don’t discuss here, because I doubt you want to support old Windows XP. But if you do, please check out the appropriate code in ffaudio yourself. WASAPI can work in 2 different modes: shared and exclusive. In shared mode multiple apps can use the same physical device and it’s the right mode for usual playback/recording apps. In exclusive mode we have an exclusive access to audio device, this is suitable for professional real-time sound apps.

WASAPI include directives must be preceded by COBJMACROS preprocessor definition, this is for pure C definitions to work correctly.

#define COBJMACROS

#include <mmdeviceapi.h>

#include <audioclient.h>Before doing anything else we must initialize COM-interface subsystem.

CoInitializeEx(NULL, 0);We must link all WASAPI apps with -lole32 linker flag.

The most of WASAPI functions return 0 on success and non-zero on failure.

WASAPI: Enumerating Devices

We create device enumerator object with CoCreateInstance(). Don’t forget to release it when we’re done.

IMMDeviceEnumerator *enu;

const GUID _CLSID_MMDeviceEnumerator = {0xbcde0395, 0xe52f, 0x467c, {0x8e,0x3d, 0xc4,0x57,0x92,0x91,0x69,0x2e}};

const GUID _IID_IMMDeviceEnumerator = {0xa95664d2, 0x9614, 0x4f35, {0xa7,0x46, 0xde,0x8d,0xb6,0x36,0x17,0xe6}};

CoCreateInstance(&_CLSID_MMDeviceEnumerator, NULL, CLSCTX_ALL, &_IID_IMMDeviceEnumerator, (void**)&enu);

...

IMMDeviceEnumerator_Release(enu);We use this device enumerator object to get array of available devices with IMMDeviceEnumerator_EnumAudioEndpoints().

IMMDeviceCollection *dcoll;

int mode = (playback) ? eRender : eCapture;

IMMDeviceEnumerator_EnumAudioEndpoints(enu, mode, DEVICE_STATE_ACTIVE, &dcoll);

...

IMMDeviceCollection_Release(dcoll);Enumerate devices by asking IMMDeviceCollection_Item() to return device handler for the specified array index.

for (int i = 0; ; i++) {

IMMDevice *dev;

if (0 != IMMDeviceCollection_Item(dcoll, i, &dev))

break;

...

IMMDevice_Release(dev);

}Then, get set of properties for this device.

IPropertyStore *props;

IMMDevice_OpenPropertyStore(dev, STGM_READ, &props);

...

IPropertyStore_Release(props);Read a single property value with IPropertyStore_GetValue(). Here’s how to get user-friendly name for the device.

PROPVARIANT name;

PropVariantInit(&name);

const PROPERTYKEY _PKEY_Device_FriendlyName = {{0xa45c254e, 0xdf1c, 0x4efd, {0x80, 0x20, 0x67, 0xd1, 0x46, 0xa8, 0x50, 0xe0}}, 14};

IPropertyStore_GetValue(props, &_PKEY_Device_FriendlyName, &name);

const wchar_t *device_name = name.pwszVal;

...

PropVariantClear(&name);And now the main reason why we need to list devices: we get the unique device ID with IMMDevice_GetId().

wchar_t *device_id = NULL;

IMMDevice_GetId(dev, &device_id);

...

CoTaskMemFree(device_id);To get system default device we use IMMDeviceEnumerator_GetDefaultAudioEndpoint(). Then we can get its ID and name exactly the same way as described above.

IMMDevice *def_dev = NULL;

IMMDeviceEnumerator_GetDefaultAudioEndpoint(enu, mode, eConsole, &def_dev);

IMMDevice_Release(def_dev);WASAPI: Opening Audio Buffer in Shared Mode

Here’s the most simple way to open an audio buffer in shared mode. Once again we start by creating a device enumerator object.

IMMDeviceEnumerator *enu;

const GUID _CLSID_MMDeviceEnumerator = {0xbcde0395, 0xe52f, 0x467c, {0x8e,0x3d, 0xc4,0x57,0x92,0x91,0x69,0x2e}};

const GUID _IID_IMMDeviceEnumerator = {0xa95664d2, 0x9614, 0x4f35, {0xa7,0x46, 0xde,0x8d,0xb6,0x36,0x17,0xe6}};

CoCreateInstance(&_CLSID_MMDeviceEnumerator, NULL, CLSCTX_ALL, &_IID_IMMDeviceEnumerator, (void**)&enu);

...

IMMDeviceEnumerator_Release(enu);Now we either use the default capture device or we already know the specific device ID. In either case we get the device descriptor.

IMMDevice *dev;

wchar_t *device_id = NULL;

if (device_id == NULL) {

int mode = (playback) ? eRender : eCapture;

IMMDeviceEnumerator_GetDefaultAudioEndpoint(enu, mode, eConsole, &dev);

} else {

IMMDeviceEnumerator_GetDevice(enu, device_id, &dev);

}

...

IMMDevice_Release(dev);We create an audio capture buffer with IMMDevice_Activate() passing IID_IAudioClient identificator to it.

IAudioClient *client;

const GUID _IID_IAudioClient = {0x1cb9ad4c, 0xdbfa, 0x4c32, {0xb1,0x78, 0xc2,0xf5,0x68,0xa7,0x03,0xb2}};

IMMDevice_Activate(dev, &_IID_IAudioClient, CLSCTX_ALL, NULL, (void**)&client);

...

IAudioClient_Release(client);Because we want to open WASAPI audio buffer in shared mode, we can’t order it to use the audio format that we want. Audio format is the subject of system-level configuration and we just have to comply with it. Most likely this format will be 16bit/44100/stereo or 24bit/44100/stereo, but we can never be sure. To be completely honest, WASAPI can accept a different sample format from us (e.g. we can use float32 format and WASAPI will automatically convert our samples to 16bit), but again, we must not rely on this behaviour. The most robust way to get the right audio format is by calling IAudioClient_GetMixFormat() which creates a WAVE-format header for us. The same header format is used in .wav files, by the way. Note that for recoding and for playback there are 2 different settings for audio format in Windows. It depends on which device our buffer is assigned to.

WAVEFORMATEX *wf;

IAudioClient_GetMixFormat(client, &wf);

...

CoTaskMemFree(wf);Now we just use this audio format to set up our buffer with IAudioClient_Initialize(). Note that we use AUDCLNT_SHAREMODE_SHARED flag here which means that we want to configurate the buffer in shared mode. The buffer length parameter must be in 100-nanoseconds interval. Keep in mind that this is just a hint, and after the function returns successfully, we should always get the actual buffer length chosen by WASAPI.

int buffer_length_msec = 500;

REFERENCE_TIME dur = buffer_length_msec * 1000 * 10;

int mode = AUDCLNT_SHAREMODE_SHARED;

int aflags = 0;

IAudioClient_Initialize(client, mode, aflags, dur, dur, (void*)wf, NULL);

u_int buf_frames;

IAudioClient_GetBufferSize(client, &buf_frames);

buffer_length_msec = buf_frames * 1000 / wf->nSamplesPerSec;WASAPI: Recording Audio in Shared Mode

We initialized the buffer, but it doesn’t provide us with an interface we can use to perform I/O. In our case for recording streams we have to get IAudioCaptureClient interface object from it.

IAudioCaptureClient *capt;

const GUID _IID_IAudioCaptureClient = {0xc8adbd64, 0xe71e, 0x48a0, {0xa4,0xde, 0x18,0x5c,0x39,0x5c,0xd3,0x17}};

IAudioClient_GetService(client, &_IID_IAudioCaptureClient, (void**)&capt);Preparation is complete, we’re ready to start recording.

IAudioClient_Start(client);To get a chunk of recorded audio data we call IAudioCaptureClient_GetBuffer(). It returns AUDCLNT_S_BUFFER_EMPTY error when there’s no unread data inside the buffer. In this case we just wait then try again. After we’ve processed the audio samples, we release the data with IAudioCaptureClient_ReleaseBuffer().

for (;;) {

u_char *data;

u_int nframes;

u_long flags;

int r = IAudioCaptureClient_GetBuffer(capt, &data, &nframes, &flags, NULL, NULL);

if (r == AUDCLNT_S_BUFFER_EMPTY) {

// Buffer is empty. Wait for more data.

int period_ms = 100;

Sleep(period_ms);

continue;

} else (r != 0) {

// error

}

...

IAudioCaptureClient_ReleaseBuffer(capt, nframes);

}WASAPI: Playing Audio in Shared Mode

Playing audio is very similar to recording but we need to use another interface for I/O. This time we pass IID_IAudioRenderClient identificator and get the IAudioRenderClient interface object.

IAudioRenderClient *render;

const GUID _IID_IAudioRenderClient = {0xf294acfc, 0x3146, 0x4483, {0xa7,0xbf, 0xad,0xdc,0xa7,0xc2,0x60,0xe2}};

IAudioClient_GetService(client, &_IID_IAudioRenderClient, (void**)&render);

...

IAudioRenderClient_Release(render);The normal playback operation is when we add some more data into audio buffer in a loop as soon as there is some free space in buffer. To get the amount of used space we call IAudioClient_GetCurrentPadding(). To get the amount of free space we use the size of our buffer (buf_frames) we got while opening the buffer. These numbers are in samples, not in bytes.

u_int filled;

IAudioClient_GetCurrentPadding(client, &filled);

int n_free_frames = buf_frames - filled;The function sets the number of used space to 0 when the buffer is full. Now for the first time we have the full buffer must start the playback.

if (!started) {

IAudioClient_Start(client);

started = 1;

}We get the free buffer region with IAudioRenderClient_GetBuffer() and after we’ve filled it with audio samples we release it with IAudioRenderClient_ReleaseBuffer().

u_char *data;

IAudioRenderClient_GetBuffer(render, n_free_frames, &data);

...

IAudioRenderClient_ReleaseBuffer(render, n_free_frames, 0);WASAPI: Draining

We never forget to drain the audio buffer before closing it otherwise the last audio data won’t be played because we haven’t given it enough time. The algorithm is the same as for ALSA. We get the number of samples still left to be played, and when the buffer is empty the draining is complete.

for (;;) {

u_int filled;

IAudioClient_GetCurrentPadding(client, &filled);

if (filled == 0)

break;

...

}In case our input data was too small to even fill our audio buffer, we still haven’t started the playback at this point. We do it, otherwise IAudioClient_GetCurrentPadding() will never signal us with «buffer empty» condition.

if (!started) {

IAudioClient_Start(client);

started = 1;

}WASAPI: Error Reporting

The most WASAPI functions return 0 on success and an error code on failure. The problem with this error code is that sometimes we can’t convert it to user-friendly error message directly — we have to do it manually. First, we check if it’s AUDCLNT_E_* code. In this case we have to set our own error message depending on the value. For example, we may have an array of strings for each possible AUDCLNT_E_* code. Don’t forget index-out-of-bounds checks!

int err = ...;

if ((err & 0xffff0000) == MAKE_HRESULT(SEVERITY_ERROR, FACILITY_AUDCLNT, 0)) {

err = err & 0xffff;

static const char audclnt_errors[][39] = {

"",

"AUDCLNT_E_NOT_INITIALIZED", // 0x1

...

"AUDCLNT_E_RESOURCES_INVALIDATED", // 0x26

};

const char *error_name = audclnt_errors[err];