Readers help support Windows Report. We may get a commission if you buy through our links.

Read our disclosure page to find out how can you help Windows Report sustain the editorial team. Read more

Microsoft recently rolled out a new Windows 10 build to Fast Ring Insiders. So, if you already got bored with the previous build, you can now install build 17604.

This new release adds a very interesting feature to the table, namely the Windows Projected File System.

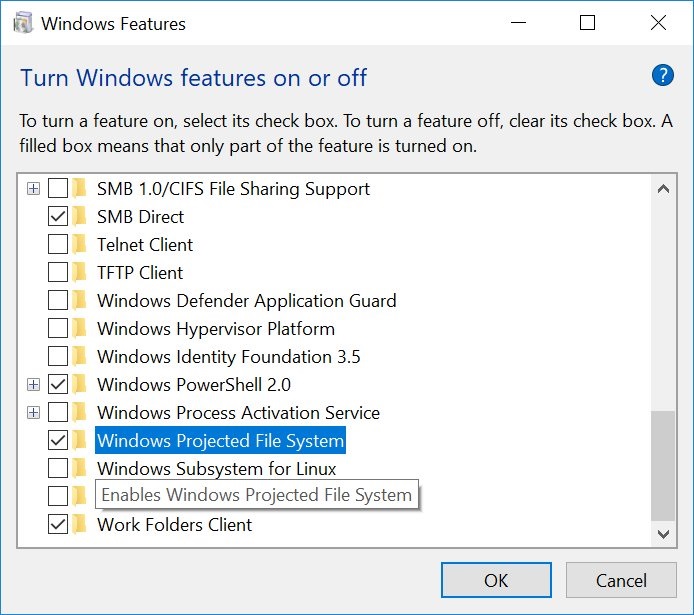

Insiders can already enable this feature by going to Windows Features > Turn Windows features on and off. All you need to do is check the Windows Projected File System box and that’s it.

Tero Alhonen also noticed this change and shared the screenshot above with the whole world on Twitter.

On the other hand, Walking Cat suggests that Microsoft renamed the GVFS (Git Virtual File System) to ProjF (Windows Projected Filesystem).

Anyway, we’ll dig more into this and update the article as soon as new information is available.

So, if you installed the latest Windows 10 build on your computer and tested the Windows Projected File System feature, tell us more about your experience in the comments below.

UPDATE:

As one of our readers explained, instead of having developers install GVFS, the Redmond giant is now including it as a feature of Windows. This corroborates Walking Cat’s hypothesis.

For more information, you can check out our reader’s comment below. Thank you, Josedolf.

Windows Projected File System is not security-related as Windows Security is focusing on Virtualization-Based Security. Windows Projected Filesystem is likely similar to what they did with OneDrive: the files are on a remote server, and you can see “placeholders”, but they’re not actually on your machine unless you open them (thus a “projected” file system).

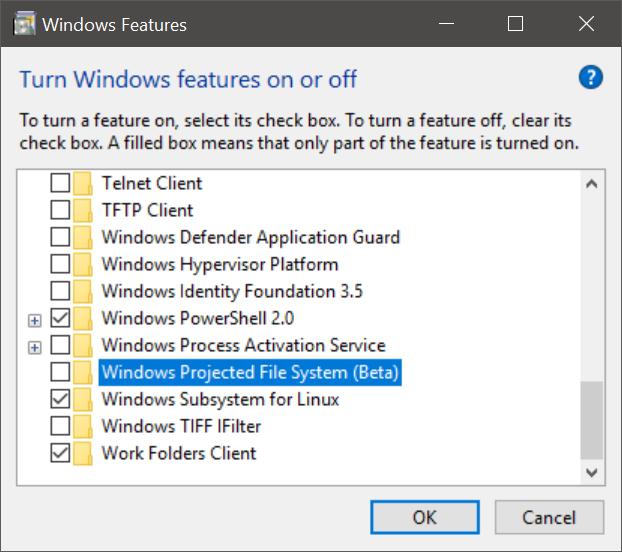

UPDATE: Just checked some Windows Insider and other developers’ Twitter accounts, and Windows Projected File System is what powers GVFS, allowing for very large repositories with little performance impact. It is marked “Beta” because there is no documentation yet.

RELATED POSTS TO CHECK OUT:

- 7 best file and folder locker tools and software for Windows 10

- Fix disappearing files and folders in Windows 10 and bring them all back

- Virtualization software: Run different operating systems on Windows 10 with these tools

Madalina Dinita

Networking & Security Specialist

Madalina has been a Windows fan ever since she got her hands on her first Windows XP computer.

She is interested in all things technology, especially emerging technologies — AI and DNA computing in particular.

Prior to joining the WindowsReport team, she worked in the corporate world for a number of years.

A little-known feature in modern Windows is the ability to expose hierarchical data using the file system. This is called Windows Projected File System (ProjFS), available since Windows 10 version 1809. There is even a sample that exposes the Registry hierarchy using this technology. Using the file system as a “projection” mechanism provides a couple of advantages over a custom mechanism:

- Any file viewing tool can present the information such as Explorer, or commands in a terminal.

- “Standard” file APIs are used, which are well-known, and available in any programming language or library.

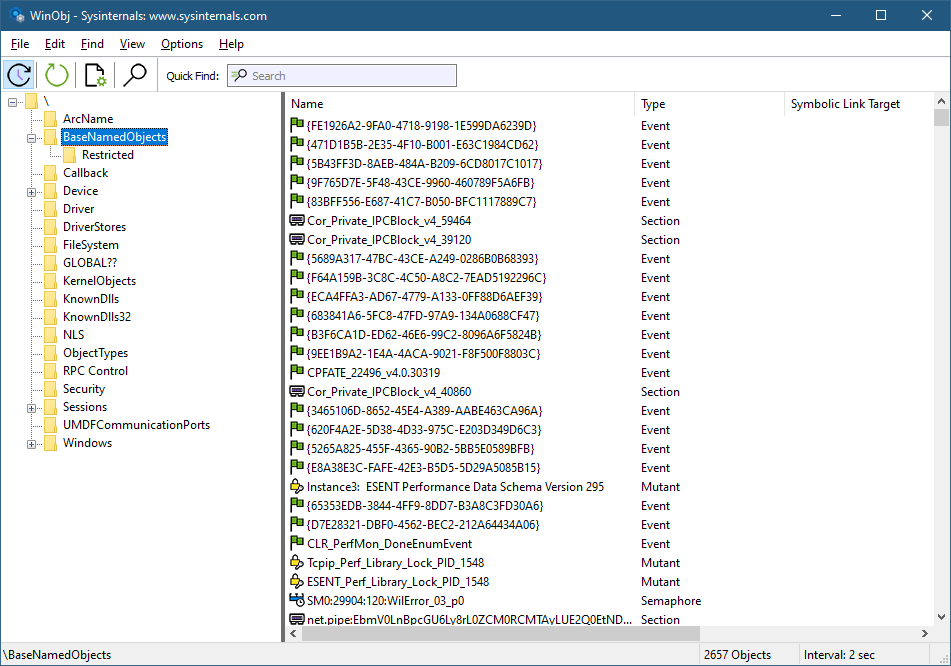

Let’s see how to build a Projected File System provider from scratch. We’ll expose object manager directories as file system directories, and other types of objects as “files”. Normally, we can see the object manager’s namespace with dedicated tools, such as WinObj from Sysinternals, or my own Object Explorer:

WinObj showing parts of the object manager namespace

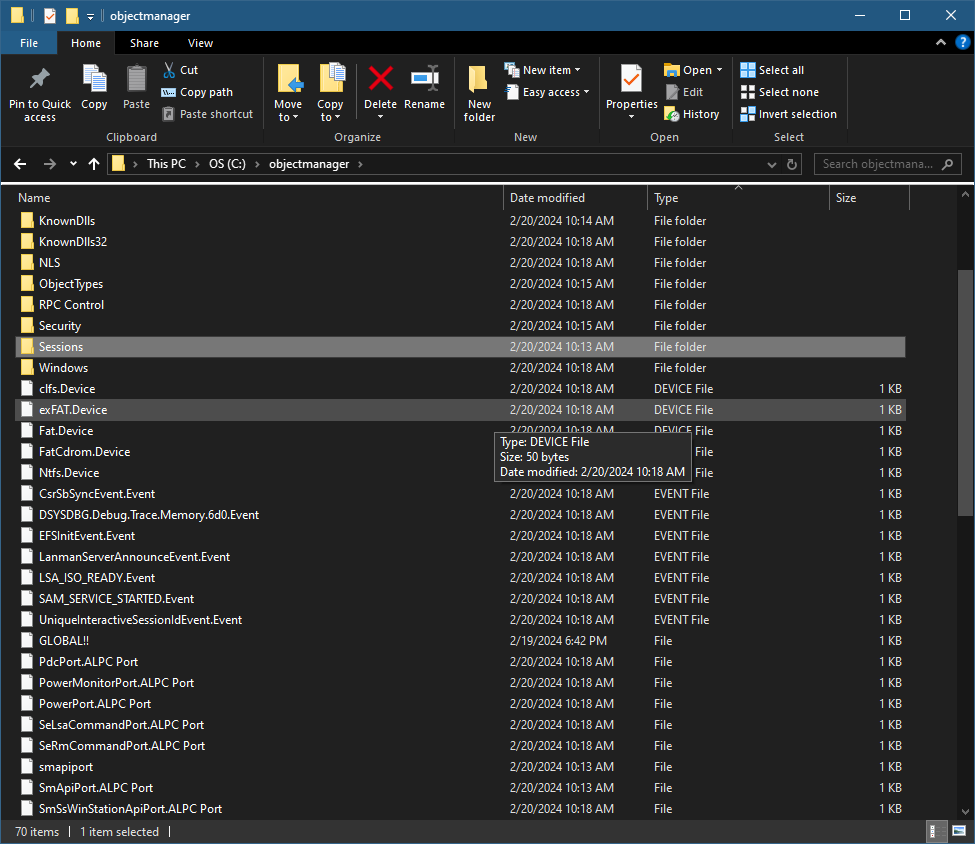

Here is an example of what we are aiming for (viewed with Explorer):

Explorer showing the root of the object manager namespace

First, support for ProjFS must be enabled to be usable. You can enable it with the Windows Features dialog or PowerShell:

Enable-WindowsOptionalFeature -Online -FeatureName Client-ProjFS -NoRestart

We’ll start by creating a C++ console application named ObjMgrProjFS; I’ve used the Windows Desktop Wizard project with a precompiled header (pch.h):

#pragma once #include <Windows.h> #include <projectedfslib.h> #include <string> #include <vector> #include <memory> #include <map> #include <ranges> #include <algorithm> #include <format> #include <optional> #include <functional>

projectedfslib.h is where the ProjFS declarations reside. projectedfslib.lib is the import library to link against. In this post, I’ll focus on the main coding aspects, rather than going through every little piece of code. The full code can be found at https://github.com/zodiacon/objmgrprojfs. It’s of course possible to use other languages to implement a ProjFS provider. I’m going to attempt one in Rust in a future post 🙂

The projected file system must be rooted in a folder in the file system. It doesn’t have to be empty, but it makes sense to use such a directory for this purpose only. The main function will take the requested root folder as input and pass it to the ObjectManagerProjection class that is used to manage everything:

int wmain(int argc, const wchar_t* argv[]) {

if (argc < 2) {

printf("Usage: ObjMgrProjFS <root_dir>\n");

return 0;

}

ObjectManagerProjection omp;

if (auto hr = omp.Init(argv[1]); hr != S_OK)

return Error(hr);

if (auto hr = omp.Start(); hr != S_OK)

return Error(hr);

printf("Virtualizing at %ws. Press ENTER to stop virtualizing...\n", argv[1]);

char buffer[3];

gets_s(buffer);

omp.Term();

return 0;

}

Let start with the initialization. We want to create the requested directory (if it doesn’t already exist). If it does exist, we’ll use it. In fact, it could exist because of a previous run of the provider, so we can keep track of the instance ID (a GUID) so that the file system itself can use its caching capabilities. We’ll “hide” the GUID in a hidden file within the directory. First, create the directory:

HRESULT ObjectManagerProjection::Init(PCWSTR root) {

GUID instanceId = GUID_NULL;

std::wstring instanceFile(root);

instanceFile += L"\\_obgmgrproj.guid";

if (!::CreateDirectory(root, nullptr)) {

//

// failed, does it exist?

//

if (::GetLastError() != ERROR_ALREADY_EXISTS)

return HRESULT_FROM_WIN32(::GetLastError());

If creation fails not because it exists, bail out with an error. Otherwise, get the instance ID that may be there and use that GUID if present:

auto hFile = ::CreateFile(instanceFile.c_str(), GENERIC_READ,

FILE_SHARE_READ, nullptr, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, nullptr);

if (hFile != INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE && ::GetFileSize(hFile, nullptr) == sizeof(GUID)) {

DWORD ret;

::ReadFile(hFile, &instanceId, sizeof(instanceId), &ret, nullptr);

::CloseHandle(hFile);

}

}

If we need to generate a new GUID, we’ll do that with CoCreateGuid and write it to the hidden file:

if (instanceId == GUID_NULL) {

::CoCreateGuid(&instanceId);

//

// write instance ID

//

auto hFile = ::CreateFile(instanceFile.c_str(), GENERIC_WRITE, 0, nullptr, CREATE_NEW, FILE_ATTRIBUTE_HIDDEN, nullptr);

if (hFile != INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

DWORD ret;

::WriteFile(hFile, &instanceId, sizeof(instanceId), &ret, nullptr);

::CloseHandle(hFile);

}

}

Finally, we must register the root with ProjFS:

auto hr = ::PrjMarkDirectoryAsPlaceholder(root, nullptr, nullptr, &instanceId); if (FAILED(hr)) return hr; m_RootDir = root; return hr;

Once Init succeeds, we need to start the actual virtualization. To that end, a structure of callbacks must be filled so that ProjFS knows what functions to call to get the information requested by the file system. This is the job of the Start method:

HRESULT ObjectManagerProjection::Start() {

PRJ_CALLBACKS cb{};

cb.StartDirectoryEnumerationCallback = StartDirectoryEnumerationCallback;

cb.EndDirectoryEnumerationCallback = EndDirectoryEnumerationCallback;

cb.GetDirectoryEnumerationCallback = GetDirectoryEnumerationCallback;

cb.GetPlaceholderInfoCallback = GetPlaceholderInformationCallback;

cb.GetFileDataCallback = GetFileDataCallback;

auto hr = ::PrjStartVirtualizing(m_RootDir.c_str(), &cb, this, nullptr, &m_VirtContext);

return hr;

}

The callbacks specified above are the absolute minimum required for a valid provider. PrjStartVirtualizing returns a virtualization context that identifies our provider, which we need to use (at least) when stopping virtualization. It’s a blocking call, which is convenient in a console app, but for other cases, it’s best put in a separate thread. The this value passed in is a user-defined context. We’ll use that to delegate these static callback functions to member functions. Here is the code for StartDirectoryEnumerationCallback:

HRESULT ObjectManagerProjection::StartDirectoryEnumerationCallback(const PRJ_CALLBACK_DATA* callbackData, const GUID* enumerationId) {

return ((ObjectManagerProjection*)callbackData->InstanceContext)->DoStartDirectoryEnumerationCallback(callbackData, enumerationId);

}

The same trick is used for the other callbacks, so that we can implement the functionality within our class. The class ObjectManagerProjection itself holds on to the following data members of interest:

struct GUIDComparer {

bool operator()(const GUID& lhs, const GUID& rhs) const {

return memcmp(&lhs, &rhs, sizeof(rhs)) < 0;

}

};

struct EnumInfo {

std::vector<ObjectNameAndType> Objects;

int Index{ -1 };

};

std::wstring m_RootDir;

PRJ_NAMESPACE_VIRTUALIZATION_CONTEXT m_VirtContext;

std::map<GUID, EnumInfo, GUIDComparer> m_Enumerations;

EnumInfo is a structure used to keep an object directory’s contents and the current index requested by the file system. A map is used to keep track of all current enumerations. Remember, it’s the file system – multiple directory listings may be happening at the same time. As it happens, each one is identified by a GUID, which is why it’s used as a key to the map. m_VirtContext is the returned value from PrjStartVirtualizing.

ObjectNameAndType is a little structure that stores the details of an object: its name and type:

struct ObjectNameAndType {

std::wstring Name;

std::wstring TypeName;

};

The Callbacks

Obviously, the bulk work for the provider is centered in the callbacks. Let’s start with StartDirectoryEnumerationCallback. Its purpose is to let the provider know that a new directory enumeration of some sort is beginning. The provider can make any necessary preparations. In our case, it’s about adding a new enumeration structure to manage based on the provided enumeration GUID:

HRESULT ObjectManagerProjection::DoStartDirectoryEnumerationCallback(const PRJ_CALLBACK_DATA* callbackData, const GUID* enumerationId) {

EnumInfo info;

m_Enumerations.insert({ *enumerationId, std::move(info) });

return S_OK;

}

We just add a new entry to our map, since we must be able to distinguish between multiple enumerations that may be happening concurrently. The complementary callback ends an enumeration which is where we delete the item from the map:

HRESULT ObjectManagerProjection::DoEndDirectoryEnumerationCallback(const PRJ_CALLBACK_DATA* callbackData, const GUID* enumerationId) {

m_Enumerations.erase(*enumerationId);

return S_OK;

}

So far, so good. The real work is centered around the GetDirectoryEnumerationCallback callback where actual enumeration must take place. The callback receives the enumeration ID and a search expression – the client may try to search using functions such as FindFirstFile / FindNextFile or similar APIs. The provided PRJ_CALLBACK_DATA contains the basic details of the request such as the relative directory itself (which could be a subdirectory). First, we reject any unknown enumeration IDs:

HRESULT ObjectManagerProjection::DoGetDirectoryEnumerationCallback(

const PRJ_CALLBACK_DATA* callbackData, const GUID* enumerationId,

PCWSTR searchExpression, PRJ_DIR_ENTRY_BUFFER_HANDLE dirEntryBufferHandle) {

auto it = m_Enumerations.find(*enumerationId);

if(it == m_Enumerations.end())

return E_INVALIDARG;

auto& info = it->second;

Next, we need to enumerate the objects in the provided directory, taking into consideration the search expression (that may require returning a subset of the items):

if (info.Index < 0 || (callbackData->Flags & PRJ_CB_DATA_FLAG_ENUM_RESTART_SCAN)) {

auto compare = [&](auto name) {

return ::PrjFileNameMatch(name, searchExpression);

};

info.Objects = ObjectManager::EnumDirectoryObjects(callbackData->FilePathName, nullptr, compare);

std::ranges::sort(info.Objects, [](auto const& item1, auto const& item2) {

return ::PrjFileNameCompare(item1.Name.c_str(), item2.Name.c_str()) < 0;

});

info.Index = 0;

}

There are quite a few things happening here. ObjectManager::EnumDirectoryObjects is a helper function that does the actual enumeration of objects in the object manager’s namespace given the root directory (callbackData->FilePathName), which is always relative to the virtualization root, which is convenient – we don’t need to care where the actual root is. The compare lambda is passed to EnumDirectoryObjects to provide a filter based on the search expression. ProjFS provides the PrjFileNameMatch function we can use to test if a specific name should be returned or not. It has the logic that caters for wildcards like * and ?.

Once the results return in a vector (info.Objects), we must sort it. The file system expects returned files/directories to be sorted in a case insensitive way, but we don’t actually need to know that. PrjFileNameCompare is provided as a function to use for sorting purposes. We call sort on the returned vector passing this function PrjFileNameCompare as the compare function.

The enumeration must happen if the PRJ_CB_DATA_FLAG_ENUM_RESTART_SCAN is specified. I also enumerate if it’s the first call for this enumeration ID.

Now that we have results (or an empty vector), we can proceed by telling ProjFS about the results. If we have no results, just return success (an empty directory):

if (info.Objects.empty()) return S_OK;

Otherwise, we must call PrjFillDirEntryBuffer for each entry in the results. However, ProjFS provides a limited buffer to accept data, which means we need to keep track of where we left off because we may be called again (without the PRJ_CB_DATA_FLAG_ENUM_RESTART_SCAN flag) to continue filling in data. This is why we keep track of the index we need to use.

The first step in the loop is to fill in details of the item: is it a subdirectory or a “file”? We can also specify the size of its data and common times like creation time, modify time, etc.:

while (info.Index < info.Objects.size()) {

PRJ_FILE_BASIC_INFO itemInfo{};

auto& item = info.Objects[info.Index];

itemInfo.IsDirectory = item.TypeName == L"Directory";

itemInfo.FileSize = itemInfo.IsDirectory ? 0 :

GetObjectSize((callbackData->FilePathName + std::wstring(L"\\") + item.Name).c_str(), item);

We fill in two details: a directory or not, based on the kernel object type being “Directory”, and a file size (in case of another type object). What is the meaning of a “file size”? It can mean whatever we want it to mean, including just specifying a size of zero. However, I decided that the “data” being held in an object would be text that provides the object’s name, type, and target (if it’s a symbolic link). Here are a few example when running the provider and using a command window:

C:\objectmanager>dir p*

Volume in drive C is OS

Volume Serial Number is 18CF-552E Directory of C:\objectmanager

02/20/2024 11:09 AM 60 PdcPort.ALPC Port

02/20/2024 11:09 AM 76 PendingRenameMutex.Mutant

02/20/2024 11:09 AM 78 PowerMonitorPort.ALPC Port

02/20/2024 11:09 AM 64 PowerPort.ALPC Port

02/20/2024 11:09 AM 88 PrjFltPort.FilterConnectionPort

5 File(s) 366 bytes

0 Dir(s) 518,890,110,976 bytes free

C:\objectmanager>type PendingRenameMutex.Mutant

Name: PendingRenameMutex

Type: Mutant

C:\objectmanager>type powerport

Name: PowerPort

Type: ALPC Port

Here is PRJ_FILE_BASIC_INFO:

typedef struct PRJ_FILE_BASIC_INFO {

BOOLEAN IsDirectory;

INT64 FileSize;

LARGE_INTEGER CreationTime;

LARGE_INTEGER LastAccessTime;

LARGE_INTEGER LastWriteTime;

LARGE_INTEGER ChangeTime;

UINT32 FileAttributes;

} PRJ_FILE_BASIC_INFO;

What is the meaning of the various times and file attributes? It can mean whatever you want – it might make sense for some types of data. If left at zero, the current time is used.

GetObjectSize is a helper function that calculates the number of bytes needed to keep the object’s text, which is what is reported to the file system.

Now we can pass the information for the item to ProjFS by calling PrjFillDirEntryBuffer:

if (FAILED(::PrjFillDirEntryBuffer( (itemInfo.IsDirectory ? item.Name : (item.Name + L"." + item.TypeName)).c_str(), &itemInfo, dirEntryBufferHandle))) break; info.Index++; }

The “name” of the item is comprised of the kernel object’s name, and the “file extension” is the object’s type name. This is just a matter of choice – I could have passed the object’s name only so that it would appear as a file with no extension. If the call to PrjFillDirEntryBuffer fails, it means the buffer is full, so we break out, but the index is not incremented, so we can provide the next object in the next callback that does not requires a rescan.

We have two callbacks remaining. One is GetPlaceholderInformationCallback, whose purpose is to provide “placeholder” information about an item, without providing its data. This is used by the file system for caching purposes. The implementation is like so:

HRESULT ObjectManagerProjection::DoGetPlaceholderInformationCallback(const PRJ_CALLBACK_DATA* callbackData) {

auto path = callbackData->FilePathName;

auto dir = ObjectManager::DirectoryExists(path);

std::optional<ObjectNameAndType> object;

if (!dir)

object = ObjectManager::ObjectExists(path);

if(!dir && !object)

return HRESULT_FROM_WIN32(ERROR_FILE_NOT_FOUND);

PRJ_PLACEHOLDER_INFO info{};

info.FileBasicInfo.IsDirectory = dir;

info.FileBasicInfo.FileSize = dir ? 0 : GetObjectSize(path, object.value());

return PrjWritePlaceholderInfo(m_VirtContext, callbackData->FilePathName, &info, sizeof(info));

}

The item could be a file or a directory. We use the file path name provided to figure out if it’s a directory kernel object or something else by utilizing some helpers in the ObjectManager class (we’ll examine those later). Then the structure PRJ_PLACEHOLDER_INFO is filled with the details and provided to PrjWritePlaceholderInfo.

The final required callback is the one that provides the data for files – objects in our case:

HRESULT ObjectManagerProjection::DoGetFileDataCallback(const PRJ_CALLBACK_DATA* callbackData, UINT64 byteOffset, UINT32 length) {

auto object = ObjectManager::ObjectExists(callbackData->FilePathName);

if (!object)

return HRESULT_FROM_WIN32(ERROR_FILE_NOT_FOUND);

auto buffer = ::PrjAllocateAlignedBuffer(m_VirtContext, length);

if (!buffer)

return E_OUTOFMEMORY;

auto data = GetObjectData(callbackData->FilePathName, object.value());

memcpy(buffer, (PBYTE)data.c_str() + byteOffset, length);

auto hr = ::PrjWriteFileData(m_VirtContext, &callbackData->DataStreamId, buffer, byteOffset, length);

::PrjFreeAlignedBuffer(buffer);

return hr;

}

First we check if the object’s path is valid. Next, we need to allocate buffer for the data. There are some ProjFS alignment requirements, so we call PrjAllocateAlignedBuffer to allocate a properly-aligned buffer. Then we get the object data (a string, by calling our helper GetObjectData), and copy it into the allocated buffer. Finally, we pass the buffer to PrjWriteFileData and free the buffer. The byte offset provided is usually zero, but could theoretically be larger if the client reads from a non-zero position, so we must be prepared for it. In our case, the data is small, but in general it could be arbitrarily large.

GetObjectData itself looks like this:

std::wstring ObjectManagerProjection::GetObjectData(PCWSTR fullname, ObjectNameAndType const& info) {

std::wstring target;

if (info.TypeName == L"SymbolicLink") {

target = ObjectManager::GetSymbolicLinkTarget(fullname);

}

auto result = std::format(L"Name: {}\nType: {}\n", info.Name, info.TypeName);

if (!target.empty())

result = std::format(L"{}Target: {}\n", result, target);

return result;

}

It calls a helper function, ObjectManager::GetSymbolicLinkTarget in case of a symbolic link, and builds the final string by using format (C++ 20) before returning it to the caller.

That’s all for the provider, except when terminating:

void ObjectManagerProjection::Term() {

::PrjStopVirtualizing(m_VirtContext);

}

The Object Manager

Looking into the ObjectManager helper class is somewhat out of the focus of this post, since it has nothing to do with ProjFS. It uses native APIs to enumerate objects in the object manager’s namespace and get details of a symbolic link’s target. For more information about the native APIs, check out my book “Windows Native API Programming” or search online. First, it includes <Winternl.h> to get some basic native functions like RtlInitUnicodeString, and also adds the APIs for directory objects:

typedef struct _OBJECT_DIRECTORY_INFORMATION {

UNICODE_STRING Name;

UNICODE_STRING TypeName;

} OBJECT_DIRECTORY_INFORMATION, * POBJECT_DIRECTORY_INFORMATION;

#define DIRECTORY_QUERY 0x0001

extern "C" {

NTSTATUS NTAPI NtOpenDirectoryObject(

_Out_ PHANDLE hDirectory,

_In_ ACCESS_MASK AccessMask,

_In_ POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ObjectAttributes);

NTSTATUS NTAPI NtQuerySymbolicLinkObject(

_In_ HANDLE LinkHandle,

_Inout_ PUNICODE_STRING LinkTarget,

_Out_opt_ PULONG ReturnedLength);

NTSTATUS NTAPI NtQueryDirectoryObject(

_In_ HANDLE hDirectory,

_Out_ POBJECT_DIRECTORY_INFORMATION DirectoryEntryBuffer,

_In_ ULONG DirectoryEntryBufferSize,

_In_ BOOLEAN bOnlyFirstEntry,

_In_ BOOLEAN bFirstEntry,

_In_ PULONG EntryIndex,

_Out_ PULONG BytesReturned);

NTSTATUS NTAPI NtOpenSymbolicLinkObject(

_Out_ PHANDLE LinkHandle,

_In_ ACCESS_MASK DesiredAccess,

_In_ POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ObjectAttributes);

}

Here is the main code that enumerates directory objects (some details omitted for clarity, see the full source code in the Github repo):

std::vector<ObjectNameAndType> ObjectManager::EnumDirectoryObjects(PCWSTR path,

PCWSTR objectName, std::function<bool(PCWSTR)> compare) {

std::vector<ObjectNameAndType> objects;

HANDLE hDirectory;

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES attr;

UNICODE_STRING name;

std::wstring spath(path);

if (spath[0] != L'\\')

spath = L'\\' + spath;

std::wstring object(objectName ? objectName : L"");

RtlInitUnicodeString(&name, spath.c_str());

InitializeObjectAttributes(&attr, &name, 0, nullptr, nullptr);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(NtOpenDirectoryObject(&hDirectory, DIRECTORY_QUERY, &attr)))

return objects;

objects.reserve(128);

BYTE buffer[1 << 12];

auto info = reinterpret_cast<OBJECT_DIRECTORY_INFORMATION*>(buffer);

bool first = true;

ULONG size, index = 0;

for (;;) {

auto start = index;

if (!NT_SUCCESS(NtQueryDirectoryObject(hDirectory, info, sizeof(buffer), FALSE, first, &index, &size)))

break;

first = false;

for (ULONG i = 0; i < index - start; i++) {

ObjectNameAndType data;

auto& p = info[i];

data.Name = std::wstring(p.Name.Buffer, p.Name.Length / sizeof(WCHAR));

if(compare && !compare(data.Name.c_str()))

continue;

data.TypeName = std::wstring(p.TypeName.Buffer, p.TypeName.Length / sizeof(WCHAR));

if(!objectName)

objects.push_back(std::move(data));

if (objectName && _wcsicmp(object.c_str(), data.Name.c_str()) == 0 ||

_wcsicmp(object.c_str(), (data.Name + L"." + data.TypeName).c_str()) == 0) {

objects.push_back(std::move(data));

break;

}

}

}

::CloseHandle(hDirectory);

return objects;

}

NtQueryDirectoryObject is called in a loop with increasing indices until it fails. The returned details for each entry is the object’s name and type name.

Here is how to get a symbolic link’s target:

std::wstring ObjectManager::GetSymbolicLinkTarget(PCWSTR path) {

std::wstring spath(path);

if (spath[0] != L'\\')

spath = L"\\" + spath;

HANDLE hLink;

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES attr;

std::wstring target;

UNICODE_STRING name;

RtlInitUnicodeString(&name, spath.c_str());

InitializeObjectAttributes(&attr, &name, 0, nullptr, nullptr);

if (NT_SUCCESS(NtOpenSymbolicLinkObject(&hLink, GENERIC_READ, &attr))) {

WCHAR buffer[1 << 10];

UNICODE_STRING result;

result.Buffer = buffer;

result.MaximumLength = sizeof(buffer);

if (NT_SUCCESS(NtQuerySymbolicLinkObject(hLink, &result, nullptr)))

target.assign(result.Buffer, result.Length / sizeof(WCHAR));

::CloseHandle(hLink);

}

return target;

}

See the full source code at https://github.com/zodiacon/ObjMgrProjFS.

Conclusion

The example provided is the bare minimum needed to write a ProjFS provider. This could be interesting for various types of data that is convenient to access with I/O APIs. Feel free to extend the example and resolve any bugs.

Ключевым преимуществом 3D-объектов является возможность обмениваться ими и совместно редактировать их с другими профессионалами отрасли, использующими различные платформы для 3D-редактирования. Справочная геометрия может быть воспроизведена в нескольких 3D-форматах и отредактирована непосредственно в папке 3D Objects в вашей файловой системе.

В следующих разделах описывается базовый рабочий процесс для редактирования файлов 3D-объектной модели вне ArcGIS Pro.

Системные требования:

- Windows 10, сборка 1809 или более поздняя

- Проецируемая файловая система Windows включена

- ArcGIS Pro открывается и работает при доступе, обновлении или замене файла 3D-модели

- Знание имени векторного слоя и идентификатора объекта (OID)

- Установлено и лицензировано стороннее приложение.

Включите Windows Projected File System

Включите Windows Projected File Systems, чтобы включить виртуальную папку 3D Objects, в которой файлы 3D-объектов открываются и редактируются с помощью стороннего приложения для редактирования.

- На панели задач Windows щелкните команду Поиск и введите отключение компонентов.

- Щелкните Включение и отключение компонентов Windows.

- Отметьте Windows Projected File System.

- Нажмите OK.

Открытие проекта

Откройте проект, чтобы отобразить 3D-объект в папке 3D Objects вашей файловой системы. Если 3D-объекты не отображаются в папке, добавьте 3D-формат к объекту, который требуется вашему стороннему приложению.

ArcGIS Pro должен оставаться открытым при доступе, обновлении или замене файла 3D-модели.

- Запустите ArcGIS Pro и откройте проект, содержащий 3D-объект, который вы хотите редактировать, с помощью стороннего приложения.

Это отобразит виртуальную папку 3D Objects в Файловом менеджере.

- С помощью Файлового менеджера перейдите во вложенную папку и убедитесь, что 3D-объект существует в 3D-формате, необходимом для вашего стороннего приложения.

Файл находится в папке с ArcGIS Pro layer name и Object ID.

Подсказка:

Используйте панель Атрибуты , чтобы определить имя слоя и идентификатор объекта.

- Если формат 3D не отображается в папке, добавьте формат к объекту.

Это реплицирует объект в папке Windows 3D Objects.

- Во вкладке Анализ в группе Геообработка щелкните Инструменты .

- В поле поиска введите добавить 3d и щелкните Добавить 3D-форматы в мультипатч.

- Щелкните стрелку Входной объект и выберите векторный слой-мультипатч, который хотите реплицировать в папке 3D Objects.

- Отметьте форматы 3D, которые вы собираетесь редактировать с помощью стороннего приложения.

- Щелкните Запустить .

Отредактируйте файл 3D-модели на месте

Запустите стороннее приложение и перейдите в подпапку с теми же ArcGIS Pro layer name и Object ID. После внесения изменений сохраните файл в том же месте с тем же именем.

Подсказка:

Кроме того, вы можете скопировать файл 3D-модели в другое место, отредактировать 3D-объект с помощью стороннего приложения, а затем заменить файл в исходной папке 3D-объектов с тем же именем.

- Запустите стороннее приложение и перейдите в подпапку с ArcGIS Pro layer name и Object ID.

- Чтобы открыть файл непосредственно в папке, щелкните файл правой кнопкой мыши, выберите Открыть с помощью и щелкните имя стороннего приложения для редактирования. Если приложение для редактирования уже открыто, перетащите файл в приложение.

- Отредактируйте 3D-объект.

- Сохраните файл 3D-модели в том же месте с тем же именем.

Отзыв по этому разделу?

Содержание

- Что такое проектируемая файловая система Windows?

- Что такое система проецируемых файлов Windows?

- 1 ответов

- Как включить Windows Projected File System на Windows 10

- Как работает Windows File Protection

- Включение и отключение компонентов Windows 10

- Как попасть в меню

- Особенности работы

- Список компонентов Windows 10

- Практическое применение

- Не работает окно компонентов

- Первый способ

- Второй способ

- Видео — Включение или отключение компонентов Windows

Что такое проектируемая файловая система Windows?

В последних сборках Windows 10 в бета-версии появилась новая функция, называемая Windows Projected File System. Я не могу найти в Google никакой информации, кроме API-интерфейсов программирования, которые не имеют смысла для меня.

Что это такое, и на каких пользователей он будет нацелен?

Проецируемая файловая система, также известная как ProjFS, — это функция, похожая на FUSE в Linux (или Dokan & WinFSP). Это позволяет приложениям создавать виртуальные файловые системы, которые кажутся неотличимыми от локальных папок, но все их содержимое генерируется программой «вживую». (Другими словами, вы видите проекции файлов, которых там может не быть.)

Основное использование ProjFS — Microsoft Git Virtual File System , дополнение к инструменту управления версиями Git, направленное на повышение его производительности и уменьшение использования дискового пространства при работе с массивными репозиториями. (Git был создан для репозиториев, содержащих только десятки тысяч файлов, таких как Linux.git; но Microsoft начала использовать его внутри для исходного хранилища Windows, которое на несколько порядков больше).

В настоящее время ProjFS, похоже, не документирована публично, но я ожидаю, что рано или поздно сторонние разработчики выяснят, как использовать его в качестве альтернативы FUSE для реализации таких виртуальных файловых систем, как sshfs , ftpfs и так далее.

Примечание: Pro J ected Файловая система не имеет ничего общего с Windows File Pro т перегиба.

Как отмечено в комментариях, документация теперь доступна для этой функции.

Что такое система проецируемых файлов Windows?

в последних сборках Windows 10, есть новая функция, в бета-версии, называется Windows Projected файловой системы. Я не могу найти никакой информации о Google, кроме программирования API, которые не имеют смысла для меня.

что это такое и на каких пользователей он будет нацелен?

1 ответов

проецируемая файловая система aka ProjFS — это функция, подобная FUSE в Linux (или Dokan & WinFSP). Это позволяет приложениям создавать виртуальные файловые системы, которые кажутся неотличимыми от локальных папок, но все их содержимое генерируется «живой» программой. (Другими словами, вы видите проекции файлов, которых может не быть.)

основное использование ProjFS является Microsoft»Git Виртуальная Файловая Система», аддон к версии Git инструмент управления, направленный на повышение производительности и сокращение использования дискового пространства при работе с огромные репозитории. (Git был создан для репозиториев, содержащих десятки тысяч файлов, таких как Linux.git; но Microsoft начала использовать его внутри для репозитория исходного кода Windows, который на несколько порядков больше.)

В настоящее время ProjFS, похоже, не публично документирован, но я ожидаю, что рано или поздно сторонние разработчики будут выясните, как использовать его в качестве альтернативы FUSE для реализации таких виртуальных файловых систем, как sshfs,ftpfs и так далее.

Примечание: Proj ected файловая система не имеет ничего общего с Windows File Protection.

Как включить Windows Projected File System на Windows 10

Компания Microsoft недавно представила предварительную сборку Windows 10 под номером 17604 в канале обновление «Ранний доступ». В этом релизе добавляется одна интересная функция под названием Windows Projected File System.

- Откройте меню Пуск > Служебные — Windows > Панель управления > Программы и компоненты > Включение или отключение компонентов Windows. Здесь поставьте галочку напротив строки Windows Projected File System (в моём случае в сборке 17110 на ней написано beta).

Защита файлов Windows File Protection (WFP) не позволяет программам заменять критически важные системные файлы Windows. Приложения не могут перезаписывать их, поскольку операционная система и другие программы пользуются этими файлами.

Microsoft представила Windows File Protection для защиты этих критически важных системных файлов и предотвращения проблем в работе операционной системы. Windows File Protection не является новой функцией Windows. Microsoft использовала эту подсистему ещё в Windows 2000 и Windows XP, вернув обратно к жизни в 2018 году.

Однако вряд ли новый механизм полагается на архитектуру 20-летней давности. Например, Microsoft переименовала GVFS (Git Virtual File System) в ProjF (Windows Projected Filesystem).

Как работает Windows File Protection

Если программа использует метод для замены защищённых файлов, WFP восстанавливает оригинальные файлы. Инсталлятор Windows подключается к WFP при установке критически важных системных файлов и делает запрос на установку и замену защищённых файлов вместо попытки установить или заменить их самостоятельно.

WFP работает главным образом незаметно в фоновом режиме. Механизм защиты запускается после того, как WFP получает уведомление об изменении файла в защищённой директории. Система заменяет изменённый файл на файл из кэша или источника установки, отменяя изменения.

Включение и отключение компонентов Windows 10

В Windows 7/10 Майкрософт сделал очередной шаг вперед в кастомизации и настройке своей операционной системы, предоставив пользователю контроль над компонентами. Теперь юзер может отключить встроенный браузер Edge или удалить лишние библиотеки для Windows Media по своему усмотрению.

Включение и отключение компонентов Windows 10

Важно! Способы перехода и работа подсистемы компонентов в Windows 7 и 10 идентичны, за исключением более обширного списка в «десятке».

Как попасть в меню

Для перехода к работе с компонентами следует выполнить несколько шагов.

- Перейдите в «Панель управления». Чтобы попасть в панель, нажмите сочетание клавиш «Win+R», наберите «control» в появившейся строке и кликните на «OK».

Набираем «control» в появившейся строке, кликаем на «OK»

В списке просмотра по категориям выберите «Программы».

В списке просмотра по категориям выбираем «Программы»

Далее перейдите в раздел «Включение/отключение компонентов».

Переходим в раздел «Включение/отключение компонентов»

На заметку! Разноцветный щит рядом со строкой означает, что для открытия потребуется администраторский аккаунт.

Для отключения компонента снимаем галочку напротив него, а для включения отмечаем компонент галочкой

Более быстрый путь потребует использования приложения для установки и удаления программ:

- нажмите «Win+R» (или «Win+S») и наберите «appwiz.cpl» в появившейся строке, кликните «ОК»;

Вводим команду «appwiz.cpl», нажимаем «ОК»

в открывшемся меню слева выберите раздел «Включение/отключение компонентов».

Кликаем по ссылке «Включение или отключение компонентов Windows»

Наконец, самый простой способ заключается в открытии меню «Выполнить» («Win+R») и наборе строки «optionalfeatures». Он приведет вас к нужной точке напрямую.

Вводим команду «optionalfeatures», нажимаем «ОК»

Особенности работы

Важно! Активируя или деактивируя элементы Windows 10, нужно ясно понимать, что именно делает тот или иной компонент. Некоторые действия могут привести к сбоям в функционировании Windows 10 и утере данных.

Набор функций реализован в виде иерархического списка. Некоторые компоненты являются составными — их можно узнать по знаку плюса в левой части.

Чтобы установить компонент, достаточно:

- поставить напротив него галочку кликом мыши, для удаления — оставить пустое поле;

Для отключения компонента снимаем галочку напротив него, а для включения отмечаем компонент галочкой

знак квадратной точки означает, что элементы составного набора установлены частично;

Знак квадратной точки означает, что элементы составного набора установлены частично

Если окно компонентов отобразилось пустым, причиной может быть отключенная служба «Установщик Windows». Активируйте ее, затем вернитесь в раздел компонентов еще раз.

Компоненты Windows не открываются

Список компонентов Windows 10

Итак, что именно из этого списка обязательно пригодится, а что можно отключить? Начнем с главного — все компоненты, кроме .NET Framework, можно отключить относительно безболезненно для системы. Смысл вынесения этих функций в отдельное меню в том, что они не обязательны для работы Windows и нужны только в строго конкретных случаях.

Таблица компонентов Windows, которые не стоит отключать.

| Компонент | Особенности |

|---|---|

| .NET Framework 3.5 и 4.7 + дополнительные службы | Набор заготовок и шаблонов для правильного функционирования операционной системы |

| PowerShell 2.0 | Вторая версия командной строки, с расширенным списком возможностей |

| Клиент рабочих папок | Синхронизация ресурсов в локальной сети, работает по дефолту |

| Компоненты прежних версий | Здесь находится DirectPlay, один из ключевых фрагментов старого DirectX. Ранее он был необходим для запуска игр, сейчас — для совместимости с устаревшими приложениями |

| Служба печати | Служба печати. Распечатка файлов, удаленное управление, работа сканера. Включены только клиентские службы, серверные нужно активировать самому |

Практически никогда не вызывает проблем остановка следующих компонентов.

Таблица компонентов Windows, которые можно отключать.

Большинство приведенных пунктов в списке выше нужны для работы сисадминов и организации локальных сетей. Обычному пользователю условный «Прослушиватель RIP» не понадобится никогда.

Практическое применение

Итак, для чего может потребоваться меню компонентов? В первую очередь это может быть установка старого или специализированного софта, который потребует для работы активацию старого протокола. В большинстве случаев Windows активирует запрашиваемый компонент сам, но иногда это придется сделать вручную.

Еще одна причина, по которой может возникнуть потребность установить компонент — появление бета-версии какой-то новой возможности. Майкрософт обычно отключает такие сервисы по умолчанию и для того, чтобы его опробовать — придется активировать пункт вручную.

Не работает окно компонентов

Пустое окно при входе в меню означает, что модуль поврежден или отключены поддерживающие его службы.

Компоненты Windows не открываются

Решается она одним из двух способов:

- с помощью командной строки;

- с помощью службы «Установщик модулей Windows».

Первый способ

- Вызовите консоль командной строки от имени администратора, кликнув правой клавишей мышки по иконке с логотипом Виндовс (или нажав клавиши «Win+X»), затем по строке «Командная строка (администратор)».

Правой кнопкой мышки нажимаем по иконке с логотипом Виндовс, затем левой кнопкой по строке «Командная строка (администратор)»

Введите «DISM /Online /Cleanup-Image /RestoreHealth», затем нажмите «Enter».

Вводим в поле команду «DISM /Online /Cleanup-Image /RestoreHealth», затем нажимаем «Enter»

Второй способ

Проверьте, активирована ли служба «Установщик модулей Windows». Для этого необходимо:

- Через встроенный поиск ввести «службы», открыть программу.

Через встроенный поиск открываем «Службы», введя в поле соответствующее слово

Найти службу «Установщик модулей Windows», раскрыть двойным левым щелчком мышки.

Находим службу «Установщик модулей Windows», раскрываем двойным левым щелчком мышки

Кликнуть по опции «Запустить», в разделе «Тип запуска» выбрать «Вручную» или «Автоматически».

Кликаем по опции «Запустить», в разделе «Тип запуска» выбираем «Вручную» или «Автоматически»

Видео — Включение или отключение компонентов Windows

| Компонент | Особенности | Изображение |

|---|---|---|

| Application Guard | Изолированная среда для работы браузера Microsoft Edge. Не дает зловредным вирусам и приложениям выбраться дальше «песочницы». Бесполезна для тех, кто не использует Edge | |

| Hyper-V | Встроенный инструмент для создания виртуальных ПК. Составной, состоит из платформы и средств управления для нее | |

| Блокировка устройства | Составной компонент, регулирующий дополнительные настройки входа в систему | |

| IE 11 | Морально и программно устаревший браузер оставлен в целях совместимости. По умолчанию включен | |

| SMNP | Устаревший протокол связи, по умолчанию отключен | |

| Identity Foundation 3.5 | Компонент фреймворка .NET, используемый некоторыми старыми приложениями | |

| Projected File System | Долгожданное обновление подсистемы Windows File Protection, защищающей от подмены ключевые системные файлы и программы. На 2018 находится в бета-версии, отключена по дефолту | |

| Веб-ядро служб IIS | Облегченная версия веб-сервера от Microsoft. Пользователю не интересна, отключена | |

| Защищенный узел | Инструменты для создания экранированной виртуальной машины на удаленном сервере | |

| Telnet | Организовывает управление командной строкой на удаленном ПК по своему протоколу. Не является безопасным, включать только при прямой необходимости | |

| TFTP | Прием/отправка данных по своему протоколу, аналогичен клиенту Telnet. Небезопасен, отключен | |

| Компоненты мультимедиа | Набор ресурсов для работы плеера Windows Media | |

| Контейнеры | В парадигме Windows контейнер — изолированное приложение, которое уже имеет все ресурсы для запуска и работы, без сторонних библиотек. Этот компонент отвечает за создание и взаимодействие с контейнерами Windows Server | |

| Мост (DCB) центра обработки данных | Серверный компонент, отвечающий за распределение трафика и повышение надежности передачи информации. Обычному пользователю нет надобности | |

| CMAK | Пакет администрирования для автоматизации клиентского подключения к VPN-серверам | |

| Печать в PDF | Создание PDF-файлов из изображений, их распечатка | |

| Платформа низкоуровневой оболочки | Запуск софта для виртуализации на уровне ядра Windows. Позволяет, к примеру, разделить сервер на несколько виртуальных машин | |

| Общий доступ к SMB/CIFS | Нужен для организации обмена данными с машинами, на которые установлены файловые системы SMB/CIFS. Применяется для сетевого использования ресурсов в устаревших версиях Windows, вплоть до XP включительно | |

| Подсистема Windows для Linux | Позволяет эмулировать ядро OS Linux в командной строке Windows. Может быть любопытно для пользователей *nix-систем и экспериментаторов | |

| Прослушиватель RIP | Сервис, обеспечивающий взаимодействие с маршрутизатором, работающим по протоколу RIP1. Применяется для крупных локальных сетей | |

| Простые службы TCP/IP | Поддержка служебных команд для отладки ЛВС | |

| MSMO | Сервис для передачи информации в нестабильных сетях. При обрыве соединения сообщение сохранится в специальном контейнере. Используется редко, в сетях крупных компаний | |

| SMB Direct | Сервис обмена данными с компьютерами, использующих файловую систему SMB 2.0. Пригодится при организации разнородной сети с Windows/Linux/Mac | |

| Служба активации Windows / Служба IIS | Несмотря на название, оба пункта не имеют ничего общего с лицензией Windows. Служба IIS позволяет размещать веб-сервера и прочие ресурсы в интернете, служба активации — помогает управлять размещением веб-приложений. Обычному юзеру не интересны | |

| Active Directory легкого доступа | Позволяет разграничивать права пользователей и проводить глубокую настройку механизма аутентификации. Полезна админам небольших сетей, не планирующим скорого расширения | |

| Службы для NFS | Еще одна файловая система, еще одна служба доступа к ней. По умолчанию отключена | |

| Соединитель Multipoint | Инструмент контроля и сбора информации для крупных сетей | |

| Средство записи XPS | Активирует обработку документов формата XPS | |

| Фильтр Windows TIFF Ifilter | Возможность распознавания и индексирования изображений TIFF. Нужна в редких случаях крупной, бессистемной базы изображений этого формата, например, после сканирования фотографий |

The Windows Projected File System (ProjFS) is a powerful technology that enables developers to create custom file system experiences in Windows. This article will explore the fundamental concepts of ProjFS, its applications, benefits, and how it can be utilized to enhance user interactions with files and folders. We will also answer some common questions regarding ProjFS, supported by insights from various research articles, including those found on ScienceDirect.

What is Windows Projected File System (ProjFS)?

Windows Projected File System is a framework that allows developers to integrate and project files stored in various locations into a unified view in the Windows file explorer. ProjFS acts as a bridge between the physical file storage and the representation of files within the operating system. It is particularly useful for applications that require access to files in a cloud storage environment or those that need to present data from non-standard locations without users needing to know the intricacies of file management.

Key Features of ProjFS

-

Virtualization: ProjFS enables the virtualization of file storage, allowing files to be displayed in Windows Explorer without the need for them to reside on the local disk.

-

Seamless Integration: Users experience a seamless integration of files from various sources, such as local drives and cloud storage, making file management more efficient.

-

Real-time Updates: ProjFS supports real-time updates, ensuring that any changes made in the actual file location are reflected instantaneously in the projected view.

Benefits of Using ProjFS

Implementing ProjFS can offer several advantages for both developers and end-users:

-

Enhanced User Experience: By providing a unified view of files, users can easily manage documents without switching between different applications or storage locations.

-

Simplified Development: Developers can create applications that simplify file management and interaction, allowing them to focus on enhancing features rather than handling intricate file system interactions.

-

Support for Diverse File Systems: ProjFS can be utilized to work with various file storage services, such as cloud-based storage, making it a flexible solution.

Practical Example

Imagine a cloud storage service that utilizes ProjFS. Users can install the application on their devices, which enables them to access their cloud files directly from their local file explorer. When a user opens a folder in the explorer that points to the cloud service, ProjFS projects the files stored in the cloud, allowing users to interact with them as if they were local files. If a user uploads a file to the cloud through this interface, ProjFS seamlessly communicates that change to the cloud service, ensuring that the file is updated without any manual intervention.

Common Questions About ProjFS

1. What file system APIs does ProjFS use?

ProjFS primarily uses the Windows File System Filter APIs to create a layer between the physical storage and the Windows shell. According to a study on ScienceDirect, these APIs facilitate the communication necessary for real-time file updates and virtualization.

2. How does ProjFS ensure data integrity during file operations?

ProjFS ensures data integrity through a robust event-driven model. This model allows it to listen for changes in both the virtual and physical file systems and synchronize them accordingly. Maintaining data consistency is critical for applications that rely on real-time data, such as collaborative tools.

3. Can ProjFS be used with existing file systems?

Yes, ProjFS can be integrated with existing file systems without requiring significant changes. For instance, developers can project cloud storage files into the local file system view without altering the cloud’s internal structure.

Future of ProjFS

With the growing demand for integrated and seamless file storage solutions, ProjFS is poised to play a significant role in the future of file system management in Windows. As applications become more data-driven and cloud-centric, leveraging ProjFS can provide developers with the tools necessary to build innovative file management solutions.

Conclusion

The Windows Projected File System is a sophisticated technology that bridges the gap between physical file storage and user interaction. With its numerous benefits, including enhanced user experience and real-time updates, ProjFS is set to revolutionize how users manage and interact with files across different storage systems. By understanding and utilizing ProjFS, developers can create powerful applications that streamline file access and enhance productivity.

References

- ScienceDirect

By leveraging the concepts discussed in this article, readers can deepen their understanding of ProjFS and explore its potential in their applications and daily file management tasks. The dynamic nature of this technology opens up new possibilities for innovation in the file system landscape.